The cross and war: Visual words

Paolo Ondarza – Vatican City

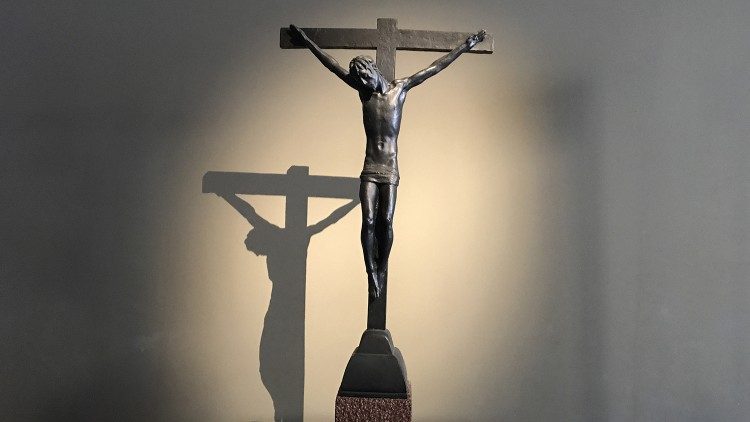

Perhaps better than words, images are capable of communicating the multiple varieties of sentiments and emotions: joy and sorrow, astonishment and melancholy, trust, fear, and desperation. This is what happens, for example, with the shock caused by the ferocity and senselessness of war – a reality that Pope Francis has not hesitated to define as “barbaric and sacrilegious.” “In the folly of war, Christ is crucified yet again,” he told the Bishops of Rome.

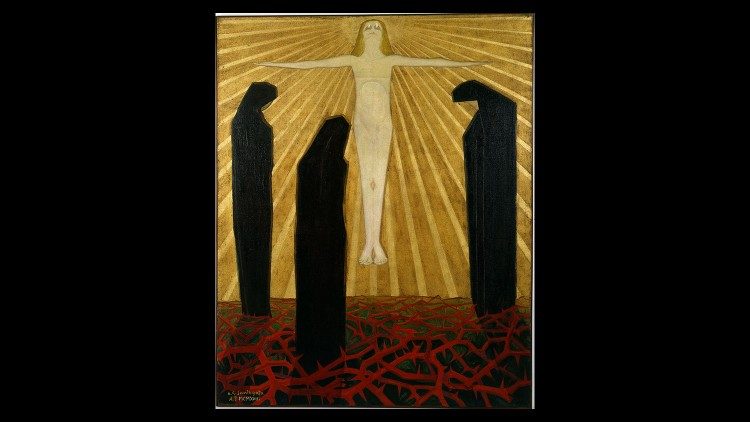

Image and Word

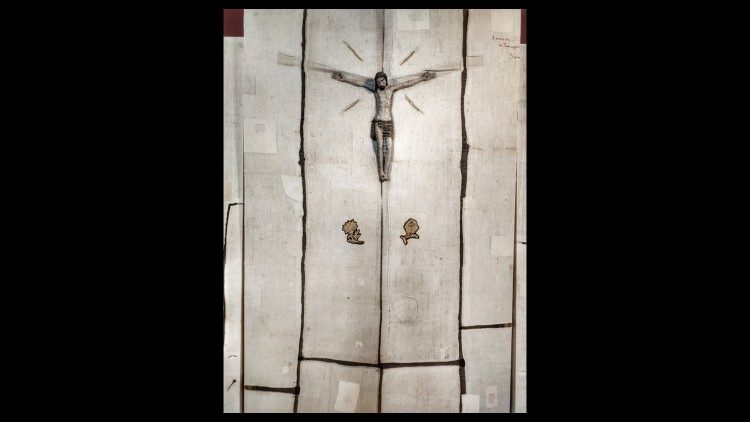

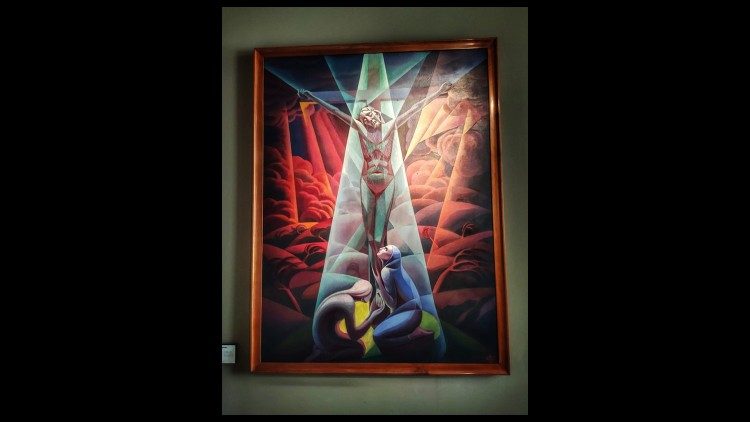

In the years between the two world wars, artists, including those who were distant from the Church, often resorted to the figure of Christ, the man of sorrows, to depict the drama of innocent victims, and the brutality of the bombings that were sowing death unconditionally. These crucifixions thus became “visual words” to express bitterness, and to protest the abuses of the dictatorships, and the struggle of man against man.

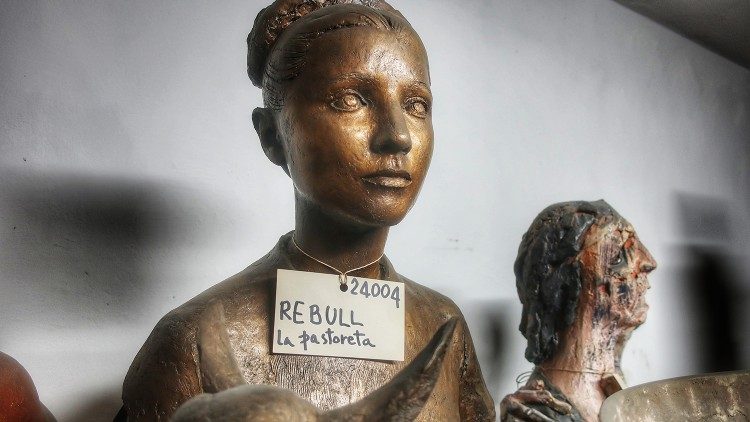

Nine thousand works

There are about nine thousand works of contemporary art in the Vatican Museums that give vivid testimony to this. They constitute what was originally called the Collection of Religious Modern Art, today called the Collection of Modern and Contemporary Art, founded by Pope Paul VI in 1973. Included in the Vatican Museums’ graphic collection of nearly four thousand works are valuable woodcuts, etchings, drypoints and lithographs. The bulk of contemporary art contained in the papal museums was mainly given by artists as expressions of gratitude to Pope Paul VI, who greatly desired to re-establish the historical, yet conflictual, link between art and the Church that had been broken the previous century.

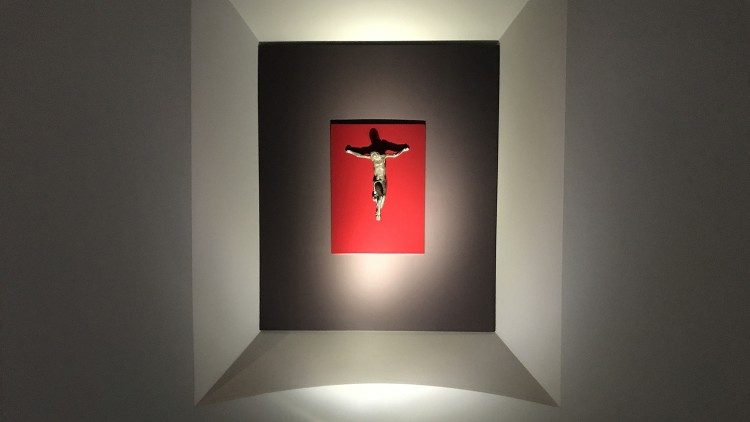

Anguish and hope

The works inspired by the Passion are stark, sometimes jarring images. They mirror the search for meaning, and the anguish experienced by so many during the years of conflict. Others, despite their starkness, manage to communicate a ray of hope along the furrows of history ravaged by hatred and death. These graphic works are exhibited in the gallery on a rotating basis or are conserved in the darkness of the storerooms of the pontifical collections. They are maintained out of the light, in rooms where the temperature is suitable for the preservation of paper, an extremely fragile medium that requires special care and attention.

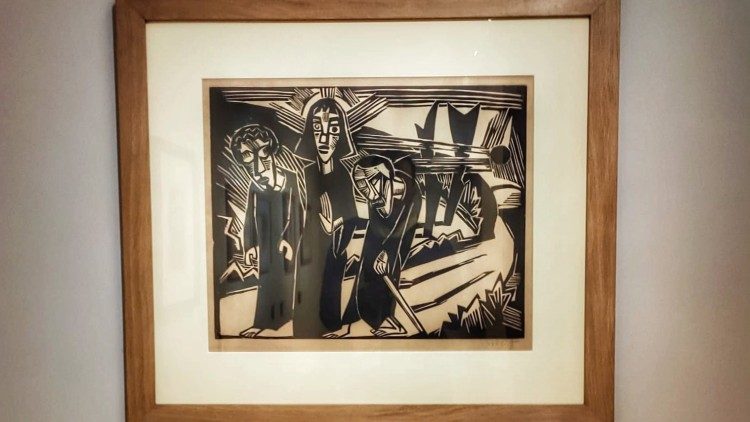

The martyrdom of the innocent

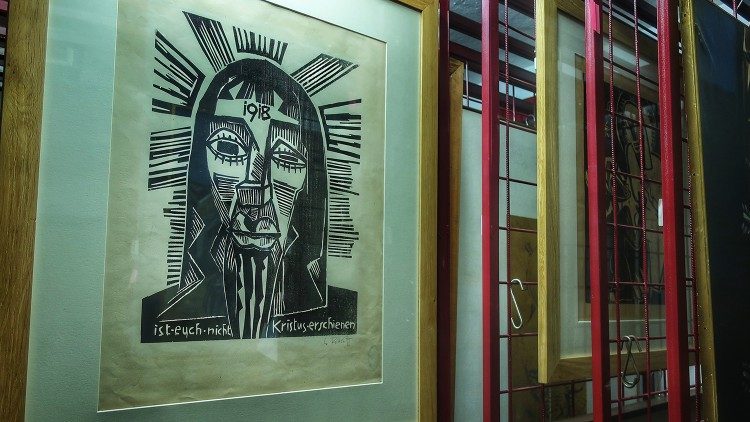

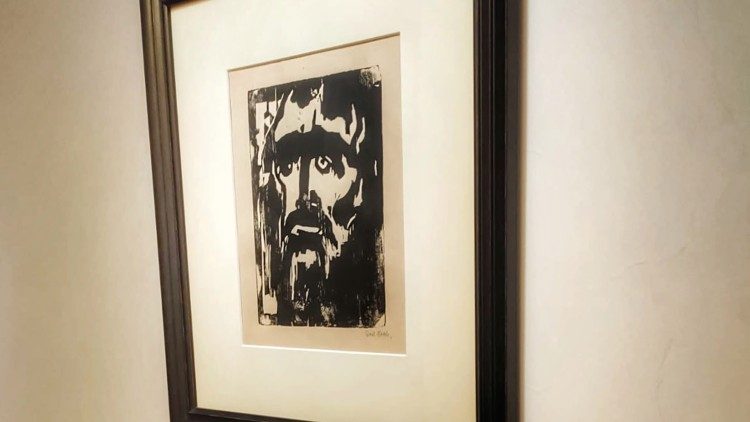

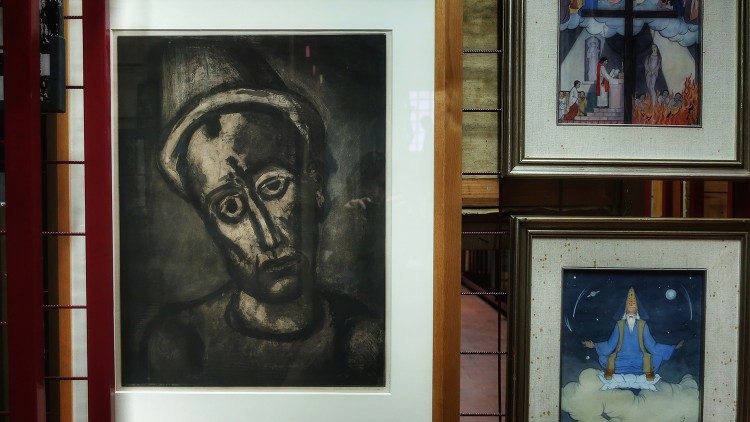

The image of a face with a closed black eye, a date tattooed on its forehead is the face of Christ by Karl Schmidt Rottluff, one of the leading figures, along with Erich Heckel and Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, of the expressionist group Die Brüke (The Bridge). He created it in Germany at the height of the Great War, which for years had been hanging over Europe like a leaden cloak. He depicts Jesus’s face, lacerated and martyred by human ferocity, in an evident and vigorous simplification of the shapes, a mix of cubist, primitive and African styles.

Rottluff, who in the first phase of his artistic production had concentrated on landscapes and nature, turned to religious subjects during the years in which he was fighting on the Eastern Front. This precious wood carving is part of a booklet depicting episodes from the life of Christ. It was published in 1918 by Kurt Wolff Verlag of Munich. It was willed by Saint Paul VI, to whom it had been personally donated by the artist, to the Vatican Collection in 1978.

Not looking the other way

“The artist’s task is to awaken doubts, sometimes to create discomfort, to amplify questions, to keep the bar high regarding ethical topics, rather than turning his or her eyes away,” explains Micol Forti, Director of the Vatican Museums' Collection of Modern and Contemporary Art. “Precisely because of this vocation, the artist cannot avoid the realm of the sacred. Art has always taken upon itself the burden of telling the story of evil that pervades history. The experience of the two world wars placed twentieth-century artists before this audacious, yet sublime, challenge.”

Infancy violated

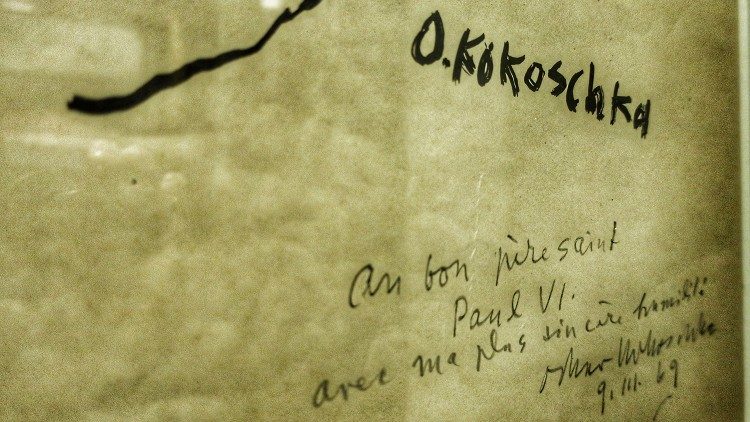

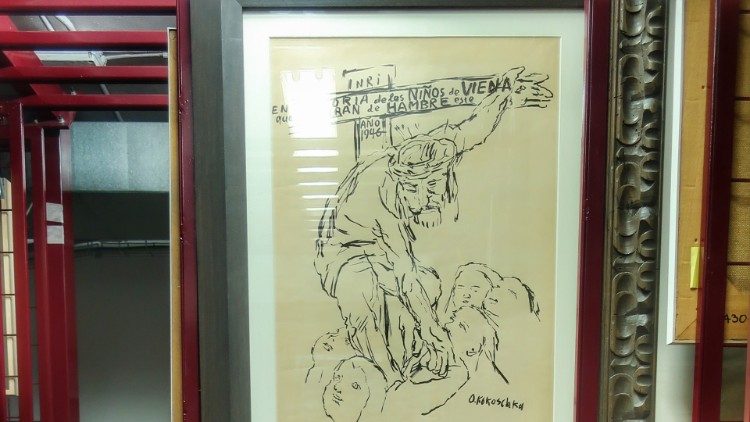

The outcry against the suffering undergone by children during these conflicts is powerfully communicated by a lithograph created by Austrian painter and playwright Oskar Kokòschka between 1945 and 1946, the years immediately following the Second World War. Containing a highly political message, it is entitled Kreuz und kinder - En memoria de los niños de Viena que moriran de hambre este año 1946 (Christ and the children – in memory of the children of Viena who will die of hunger this year 1946). It depicts Christ extending his hand to the children standing at the foot of his cross. 5,000 copies were printed and posted in the Underground stations in London to collect funds for Czechoslovakian war orphans.

Art is a means of diffusion; it communicates a message that breaks barriers. A handwritten dedication attests that this work was donated by the artist to Pope Paul VI.

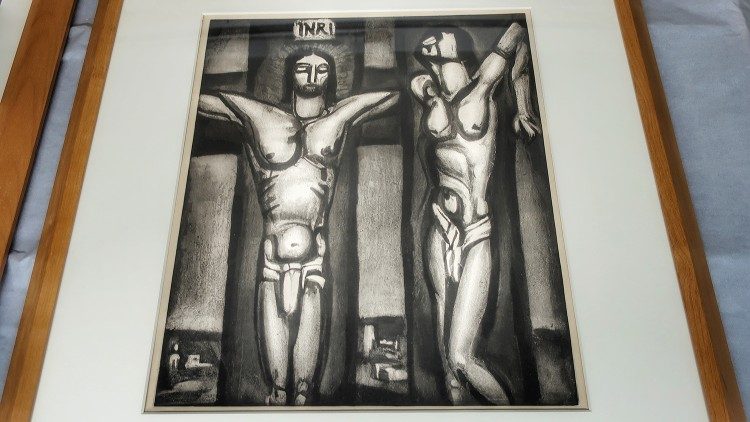

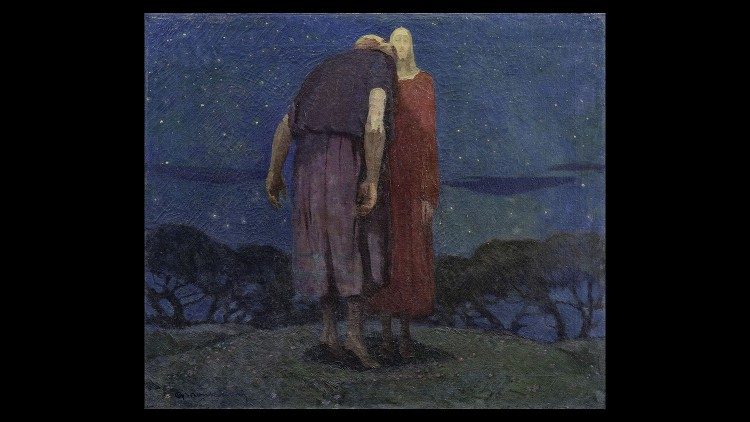

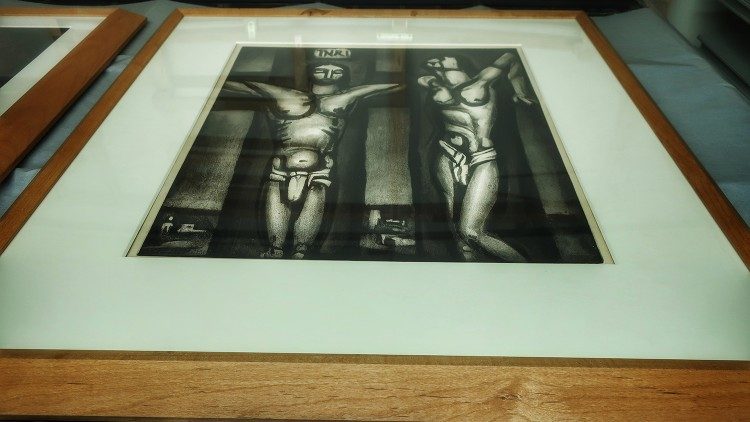

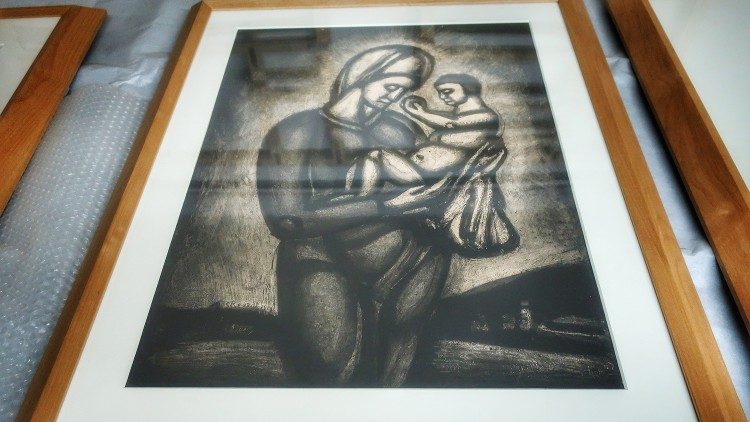

Christ in the least

Georges Rouault created a series of 58 lithographs produced between 1912 and 1948 on the theme Miserere. The thread running through them is the most famous of the penitential Psalms, Psalm 50, in which King David asks God pardon for his sins. The artist, himself a believer who was ever attentive to the weakest and lowest of humanity – prostitutes, the homeless, street performers, people who were alone or abandoned – preferred to use this graphic technique which allowed him to reach the largest possible audience, including the lower classes. This project followed a very complex and lengthy editorial process at the conceptual level, and took over thirty years to complete. The series also includes scenes inspired by war, death and the Passion.

“France was already a secularized society in 1905, the year in which the law of the separation of Church and State was introduced,” Micol Forti continues. “Rouault met often with a coterie of secular artists who held positions at variance with the Church, but who nevertheless chose styles strongly linked to its traditional iconography. Thus, assuming these sacred themes became a means for civil engagement, without the social theme ever overpowering the underlying sacred one. In these works, Christ embodies ‘man’ and the least.”

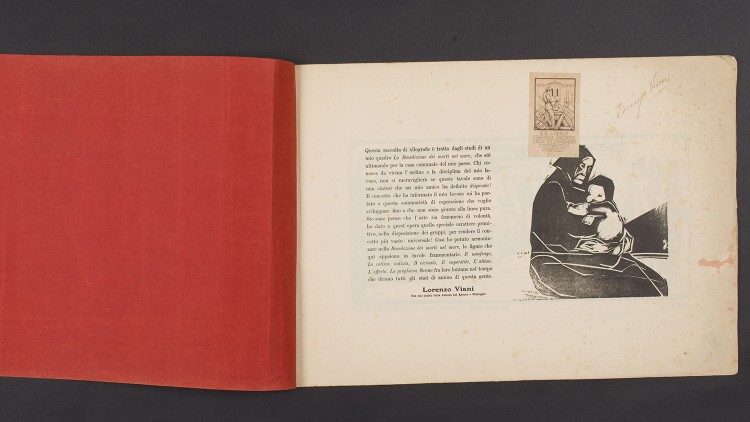

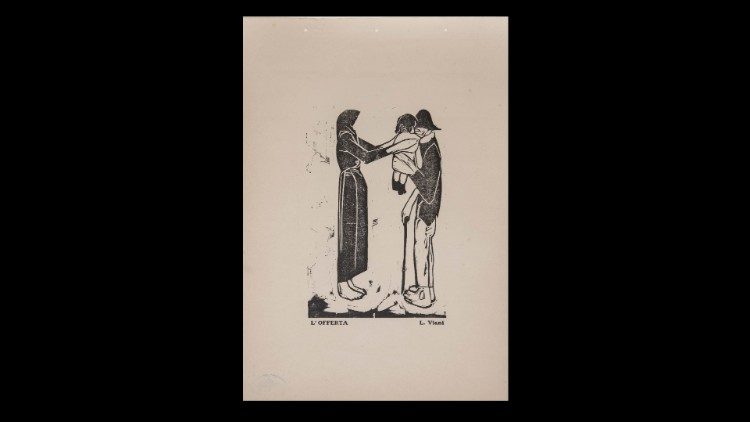

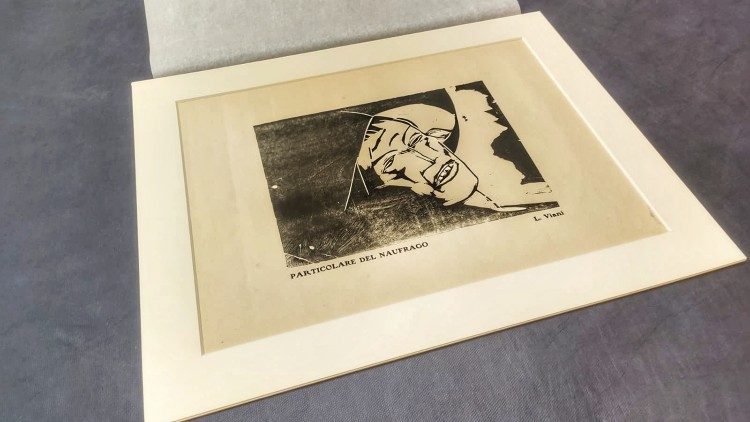

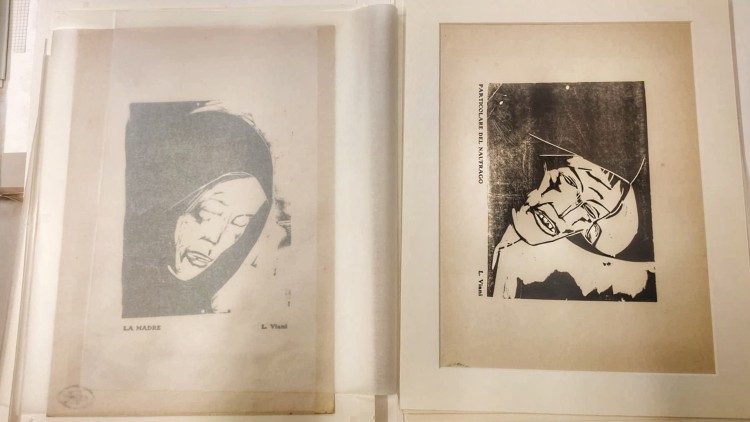

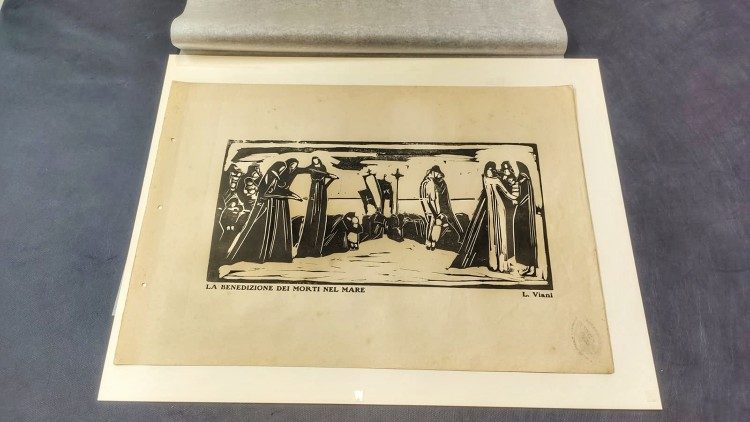

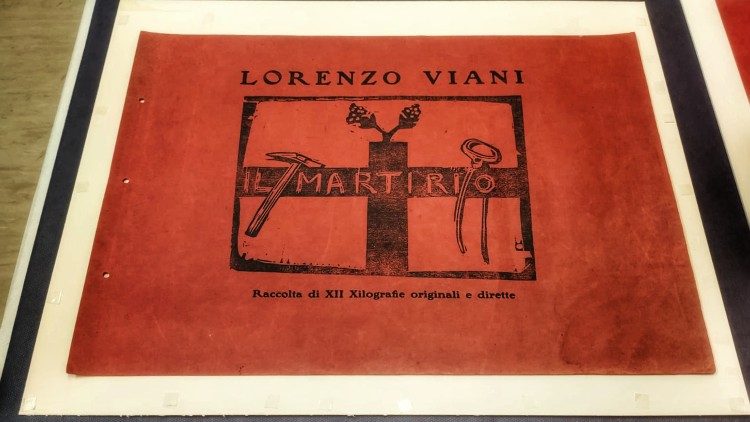

The tragedy of the dead at sea

Quotations from the Gospels, or figures connected to popular piety and the devotional practice of the Way of the Cross, are present in a series of still highly relevant graphic works. These are xylographs, images created by engraving wood, created between 1912 and 1913. They were published in 1918 by Lorenzo Viani. They depict the blessing of the dead at sea, an experience that particularly touched Viareggio, the hometown of this Italian painter and poet who depicts, like modern Pietas, women mourning their sons or husbands lost at sea. These mothers are veiled, grief-stricken, veterans of the exhausting toil of fishermen on a voyage mowed down by death, which is depicted in all its cruelty on the faces of the shipwrecked corpses. His designs bear obvious hints of African art, as well as Italian medieval Pisan art.

Synthetic and terse, these representations depicting concrete, real-life experience, decry the innocent death caused by the drudgery of work in wartime. “The morning after Italy entered the war in 1915,” Micol Forti recalls, “Ravenna was bombarded unexpectedly. An echo of this shocking event reached Viareggio. The inclusion of these works within the social and collective fabric is evident, and is communicated using Christian iconography.”

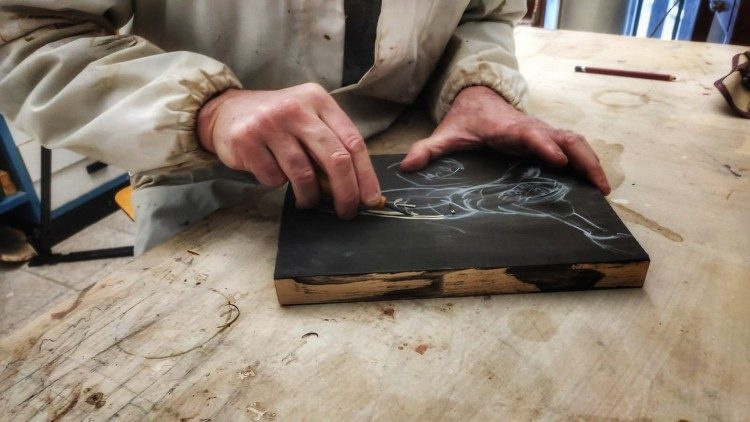

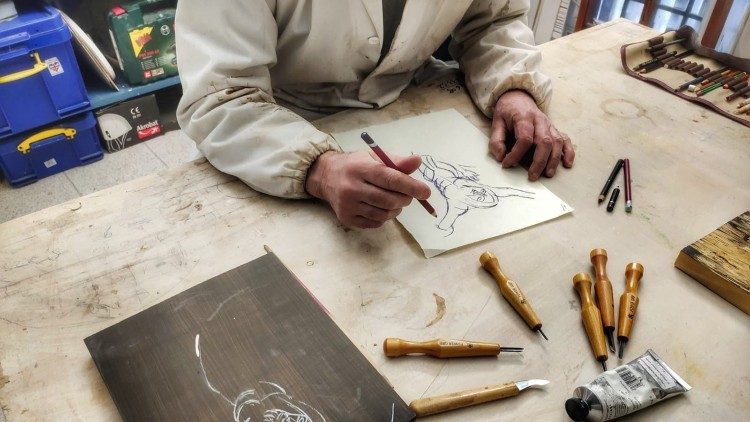

Mary: 'Everywoman'

“The wooden originals of these sheets still exist.” Viani used a gouge, a particular type of chisel with a concave blade. “It seems like he was chiseling indecipherable hieroglyphics. But the moment the image is transferred onto paper, the images take on the delicacy and poetry of the figure of the Madonna in mourning, the image of ‘everywoman’ in the world.”

Thirteen engravings by the Spanish artist José Ortega, inspired by the Spanish War of 1936 and by the 16th century prints of Albrecht Dürer, are in dialogue with the great European artistic tradition of the past. A black background, and outlines of the drawing in white, provide a contrast, emphasizing the violence of the bombings during those agonizing years.

Horrors of the death camps

An abomination, an abyss, the agony, the insane and bleak reality of the concentration camps are evoked in all their cruelty and bleakness in the drawing of Francesco Messina done in 1977: from the nude, defenseless, skeletal corpses, reduced to nothing by the sufferings endured, to the mute, anguished gazes of the innocent detainees. This is the inspiration behind six bronze reliefs exhibited in the gallery dedicated to the Passion, which depict “the Horrors of the War” where men kill each other, prisoners of the barbed wire that confines them. Christ’s martyrdom, representing all the injustices and evils in the world, of their absorption and redemption, is made real once again by Messina who depicts a woman crucified upside down, or two men fighting like Cain and Abel. “The reflection transcends the circumstance,” Micol Forti comments. “As we well know, there have always been wars in our world. Each one is only the bearer of death and tragedy. Therefore, drawing attention to it, our participation by recalling it, are fundamental so they won’t be replicated in the future.”

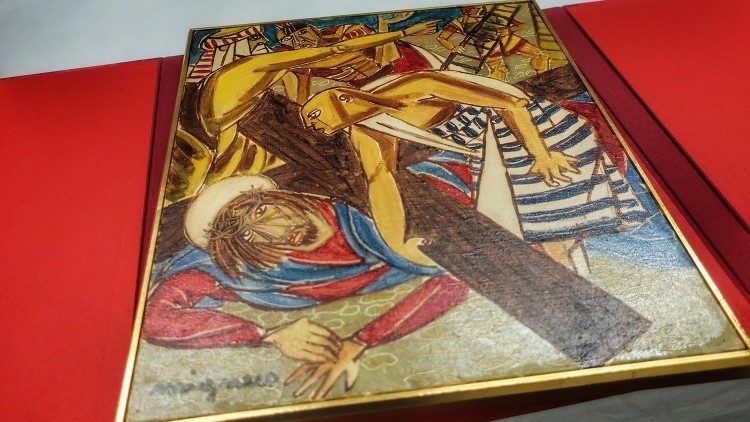

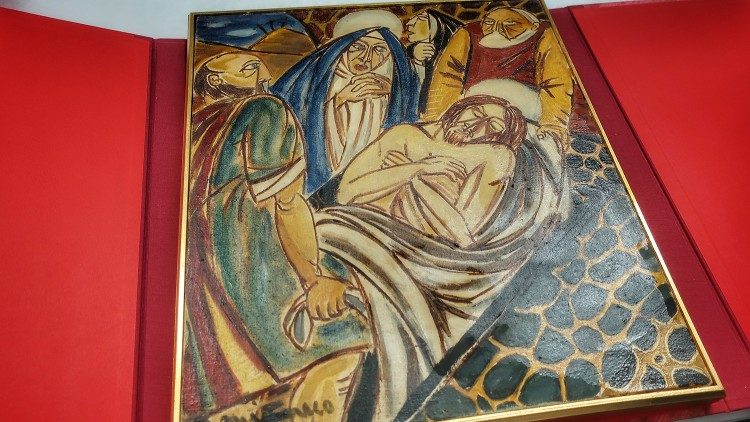

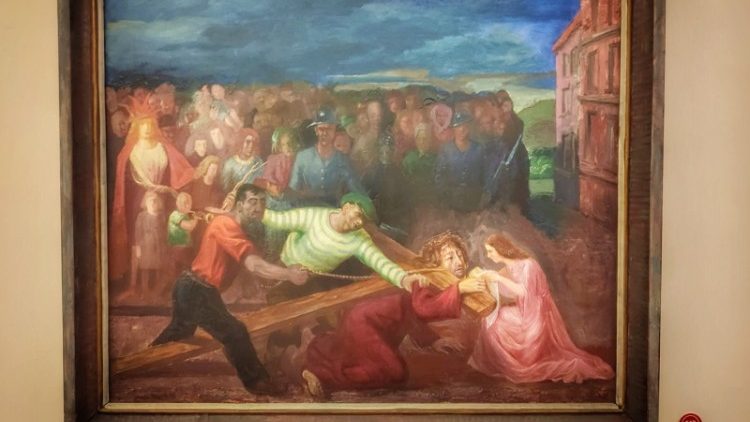

Carved painting

Giuseppe Migneco created a Way of the Cross, intense with its strong and vivid colors, and its shapes formed with sharp, crisp strokes. “A wood carver who carves with a paintbrush,” one of his admirers called him. “It is a post-war work. We do not know the exact date it was created, but it can be dated to the early 1950s. Unused to producing such images, Migneco created these fourteen Stations for a collector who subsequently departed for Argentina. They were never published.”

Art, prophecy and poetry

The works analyzed to this point are vivid proof of the fact that what many have wrongly defined as “the divorce between art and the Church” never happened. Even Paul VI, who celebrated the Mass with artists in the Sistine Chapel on 7 May 1964, believed that the link should never be broken, but should be nurtured and cultivated. It is a task just as relevant as ever despite the secularization of the arts in recent decades. The original thousand works that formed the founding nucleus of the section dedicated to contemporary art has increased to nine thousand works donated by artists to the Vatican Museums. The collection already includes approximately five hundred works donated after 2001, confirming that the area of sacred art remains a rich source of inspiration. Pope Paul VI defined artists as “prophets” and “poets,” teachers who make “visible” what is “invisible.” “If we seek Christ where He truly is – in heaven,” he told them, “we would see him reflected, we would find him throbbing, in our souls. The transcendent God has, in a certain sense, become immanent, has become the interior friend, the spiritual master.”

“The artist who is open to the sacred,” concludes Micol Forti, “is certainly one who is invested from the point of view of content, and who is not content to please on a merely esthetic level. Even Picasso, who always maintained his distance from the Church, portrayed religious images and the ever-present image of the crucifixion.” For, it is “only in the mystery of the incarnate Word,” states Gaudium et Spes, that “the mystery of man takes on light.”

Thank you for reading our article. You can keep up-to-date by subscribing to our daily newsletter. Just click here