The invisible and indelible wounds of war

By Alessandro Gisotti

In 1981, a young Italian-American psychiatrist founded the Harvard Program in Refugee Trauma, in Boston, a pioneering programme on the mental health care of survivors of mass violence and torture. More than 40 years later, Dr. Richard F. Mollica and his team of experts are committed to helping victims of the most brutal violence cope with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

From Cambodia to Lebanon, from former Yugoslavia to Rwanda, from East Timor to Afghanistan, Dr. Mollica has assisted women, men and children traumatised by violence, fear and tragic events, an experience which he narrates in his book entitled, “Healing Invisible Wounds. Path to Hope and Recovery in a Violent World”.

He is Professor of Psychiatry at Harvard Medical School, Director of the Harvard Program in Refugee Trauma, and one of the world’s leading experts in the research and treatment of serious mental disorders.

In the following interview with Vatican Media, he speaks about the damaging consequences of war on individuals and communities.

Although the wounds are indelible, the Harvard psychiatrist explains that with patient work, acceptance, listening and empathy, one can regain the joy of life and hope for the future.

Q: In March 2022, one month after the beginning of the war in Ukraine, the scientific review “The Lancet” wrote that, after the deaths, the greatest harm to the population is post-traumatic stress, which will last long after the end of the conflict. Are these wounds invisible yet indelible?

The wounds of mass violence are enormous and their impact on the health and mental health of a trauma survivor can last a lifetime. Numerous scientific studies over the past 50 years have shown that the prevalence of mental health problems in conflict-affected civilian and refugee populations can be high. Almost all citizens in a war zone experience massive anxiety, sadness, and distress.

Special attention needs to be given to children and adolescents. In the conflicts of mass violence that exist today, children and adolescents are deeply affected by violence including physical harm, death of loved ones, and forced displacement. In Ukraine, where we are introducing a trauma-informed care approach in collaboration with Ukrainian educators, over 50% of the displaced students who entered the school educational program had moderate to severe anxiety, fear, and depression.

Fifty years ago, European and American psychiatry believed that survivors who had experienced extreme violence were incurable and would not benefit from mental health care. After five decades of research and clinical care, this early belief that the invisible wounds of mass violence are indelible have proven to be false. Deep listening to the trauma story of survivors — adults, teens, and children — is a central core of effective mental health care. Creating a safe and secure space and home life, especially for children, is essential.

Q: What is the pivotal point in this difficult healing process?

Learning to control and regulate empathy is critical. Too much empathy can cause emotional distress in the listener/healer; too little empathy can cause a poor relationship. Teaching the survivor the use of deep breathing when anxious and distressed is one of the most valuable of all healing instruments.

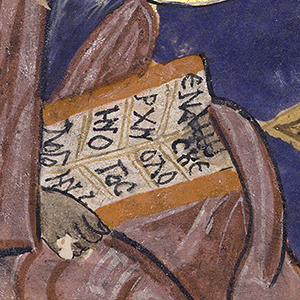

In line with Pope Francis’s thinking, spirituality, prayer and ritual, including connecting with nature, green space, and animals, can be very therapeutic. In our clinic and in Ukraine schools, we recommend that all patients and students carry an image of an animal they love. For many religious people it can be an image of a religious symbol such as the white dove of the Holy Spirit for Catholics. In our research the major factors associated with self-healing—altruism, work/study, social connections, and spirituality—need to be supported and even put into a medical prescription.

Finally, storytelling and comforting activities need to be encouraged, not only with parents and children, but also with teachers and health practitioners. The caretakers can encourage the kids to read fables and folktales together, tell a story with finger puppets, colour a picture, sing a song or listen to music.

Q: You have dedicated your life to healing these invisible wounds in dramatic contexts of war, from the former Yugoslavia to Cambodia. What is the most important lesson you have learned from this experience?

The most important lessons learned after years of listening to trauma survivors is that humiliation is the major weapon of violence. The violent perpetrator (observe the current wars) uses the instruments of humiliation to create the state of humiliation. The goal of the perpetrator is to create through humiliation the complete annihilation of the person, their family, community, society, and nation.

The instruments of humiliation include rape and other forms of gender-based violence. In most societies, once a woman is raped, it not only destroys the victim of rape but also the family, leading to tremendous shame and stigma. The captivity and torture of soldiers and civilians through horrific, degrading, and inhumane acts of violence leads to deep humiliating injuries.

Q: The wounds on children, especially girls, are even more terrible…

Children and teenagers not only experience mass violence indirectly, but also directly. Young girls are commonly raped and sexually abused; children are trained and used as child soldiers and initiated into killing. Children and adolescents are forced to witness the degradation and humiliation of their parents and their loved ones.

When a child witnesses the violent abuse of a father, for example, the seed of anger and revenge is placed within the child to be activated when he grows up. The state of humiliation is buried within the trauma survivor and can not only not be recognized by others, including doctors, but also by the survivors themselves.

Unfortunately, the mental health field has until recently failed to acknowledge the powerful destructive impact of this emotion. All attempts must be made to overcome humiliation and restore the trauma survivor to human dignity. The spiritual power of the Church can play a major role in the recovery process.

Q: Pope Francis has underlined many times that to heal the wounds of our humanity we must first listen to the suffering of others. For those who work in your field, is listening essential?

My book, Healing Invisible Wounds, tried to make the invisible wounds of mass violence visible. As Pope Francis has highlighted, the major barrier that maintains the invisibility of great human suffering is the reality that most family members, neighbours, and society itself actively deny and turn away from listening to the survivor’s trauma story.

Yet, deep listening to the trauma story—that is, the traumatic life experience of the survivor, in their own words—is the core of the healing experience and a major incentive for the prevention of violence. The great Italian biographer of the concentration camp experience, Primo Levi, shares with us his dream that when he returns home and tries to share his experience with his sister, she turns away. This turning away from the trauma story is also commonly witnessed in health care professionals.

The doctors, like many of us who are untrained in medical care, can find the survivor’s story too painful to hear, or we might be afraid the storyteller will become unbearably upset telling us their story. Also, we may have no idea how to offer compassionate counseling and support to the storyteller.

Q: In your book you also underline the power of storytelling as a way of healing…

In our Boston clinic, over the past 40 years, we have listened to over 10,000 trauma stories of extreme violence, with remarkable healing results. Storytelling and deep listening can take many forms and can be everything from a simple basic conversation to the telling of stories through fables, parables, poetry and the expressive arts. The story allows us to find the person behind the brutal facts of the trauma story.

Storytelling and reflective writing have been demonstrated to heal chronic pain from arthritis and bring relief from other chronic ailments. But all evidence reveals the most powerful healing instrument is when the storyteller tells his story to another person. The listener becomes part of the story; and not only has the joy of listening (along with the pain) but also the joy of absorbing the deep wisdom, resiliency, and spirituality of the storyteller. Listening to the trauma story is a gift to be shared of the real beauty that emerges out of sharing our traumatic life experiences.

Q: When a soldier comes home with severe mental disorders, the whole family somehow gets sick. How do you manage to take care of these people while trying to maintain the stability of the rest of the family?

Veterans take home to their families all of the stressors and tragedies they have experienced as warriors. Many have “survivor guilt” because a close comrade in combat has died and they feel guilty for having survived.

One of the major issues causing the high prevalence of depression and suicidal thinking in veterans is the experience of moral injury. Moral injury occurs when a soldier does something he believes is morally wrong but is fully sanctioned as morally justified by the military and society. Moral injury is prevalent in the emotional lives of soldiers and veterans and can be a very destructive emotion. Unfortunately, the veteran and their family members have little knowledge of the great long-term suffering caused by the experience of violence during wartime.

The brutality of traumatic head injury causes major damage to the brain that can destroy a soldier’s personality and social functioning and can have enormous impact on their family members. The entire family is necessary to assist a veteran in their recovery. The family, including children, close relatives, and even pets, needs to be fully involved in the healing process.

Spiritual advisers and religious ceremonies can play an important role in healing moral injury. There are certain tragedies, such as the mistaken killing of a child, that can only be forgiven by a Holy Presence.

Q: In the face of evils as huge as war or brutal violence, we feel helpless, defenseless. How can we protect ourselves from this feeling of despair?

Often the catastrophic global situations of mass violence, climate change, and ecocide, the destruction of our natural world, make us as ordinary citizens feel helpless. It is important that every person fights against the hopeless despair stimulated by the enormity of the problem.

First, it can be recognized that there are millions of small groups globally doing good in the world. I believe that our small clinic is one of these groups. Pope Francis is a spokesman of hope for these groups. The medical and public health narrative needs to be changed to one of hope that trauma survivors can be healed and violence can be prevented. This scientific reality needs to be socially recognized. Our focus over the past forty years has been to create beautiful healing environments even in the most violent and impoverished situations.

Q: Is there a story, in so many years of experience, that represents the synthesis of your work and that you feel you can also share as a sign of hope for the many who are suffering right now in so many places in the world because of war and violence?

In the Cambodian refugee camp called Site 2 on the Thai-Cambodian border in the early 1990s, our team discovered in the most desolate of places the Khmer People’s Depression Relief Unit (KPDR). KPDR, in spite of the total lack of everything, created a beautiful garden, small bamboo bedrooms, and a traditional healing center for steam baths and coining, and a Buddhist sanctuary for prayer and meditation. Out of very little, the Cambodian staff created a beautiful healing environment.

During one of our visits to KPDR, I met a young boy whose parents had been killed by the Pol Pot regime. He was blinded fleeing into Thailand and ended up in the Site 2 refugee camp. This young boy felt hopeless; he did not want to live. When I met him for the first time at KPDR, I felt hopeless for him. Two years later, after living in a bamboo hut at KPDR, he had found a new life for himself. He was active and felt his life was on a meaningful journey.

Q: You have a mantra in your clinic in Boston: “There is no healing without beauty.”

In our clinic in Boston, and everywhere we have worked (in Cambodia, Peru, Liberia, Lebanon, and Italy) we have learned the power of having trauma survivors create beautiful healing environments for themselves. Recently, in spite of the current gang violence in Haiti, with the efforts of a charismatic Haitian priest, we have created a beautiful healing environment built by Haitian architects for Haitian women and children fleeing the violence.

This new center has a garden, childcare, a place for prayer, family therapy rooms, and a bird sanctuary. It is a safe and secure space where Haitian women and their children, surrounded by songbirds and nature, can retreat themselves from the fear and anxiety of living in a violent world. Each visitor is asked to plant a tree around the center as a celebration of the healing power of nature.

Tremendous healing beauty also exists not only in physical aesthetic spaces but also in moral behaviour. Creating moral beauty by acting virtuous and creating good in the world is a key to hope and the restoration of human dignity. All healing of violence and the prevention of violence is based upon the restoration of human dignity and the social and political acknowledgement that all life is sacred, including the plants and animals.

Violence is unacceptable at all levels of society. And as St. Augustine preached, injustice is ugly. Our goal is to live and create a just and more empathic world. We are in fact biologically wired to achieve this social miracle.

Thank you for reading our article. You can keep up-to-date by subscribing to our daily newsletter. Just click here