“The wall inside my head”

Jean Charles Putzolu - Banská Bystrica

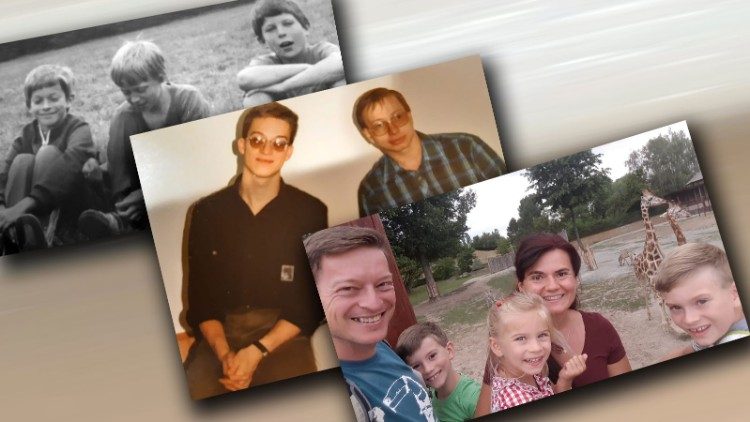

Today Pavel Miksu is 44 years old. He is a happy family man. He lives in Brno, Czech Republic, where he works as a journalist. He has bad memories of his youth under the yoke of the communist regime, he says. In the industrial town of Přerov in Central Moravia, where he lived with his parents, the local people backed the Communist Party. "Our family was Catholic and this alone was a problem. My parents were always having to explain their belief: why they were Christians, why they practiced their faith...". The regime did not tolerate religion and the mere fact of being a Christian was an obstacle. Pavel's sister, for example, was barred from attending university. His father, an engineer credited with scientific achievements, never got a promotion throughout his career. He occupied the same desk for 40 years. "In every company, in every school, there were the politruk, employees in charge of controlling their colleagues. That was their job. It was official. They had to guarantee that party ideas were obeyed. If anyone expressed a different idea, they immediately had problems”. Pavel explains that the politruk prevented many categories of people from living a "normal" life. Intellectuals in particular. And many priests too. The secret police constantly monitored the few churches that were still open. Entering a place of worship could cause problems for anyone. Praying was barely tolerated. Expressing one's faith in public was strictly forbidden. Dealing with a social problem could lead to arrest. Pavel recalls how the secret police “photographed and filmed all those who dared to practice their faith when there were large gatherings, like the few authorized pilgrimages”.

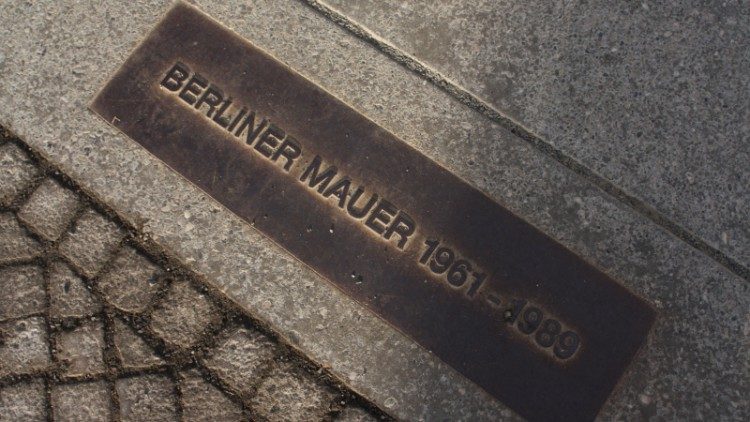

The fall of the Berlin Wall

For the vast majority of people, it came as a huge surprise. But for those who were in the least bit informed, it was different: you could perceive a certain nervousness among the Communist Party leaders. In fact, party officials who well aware of the situation, had already understood the first signs. "They knew they wouldn’t last long", says Pavel. "For me, everything changed. Immediately", he continues. "In my child’s mind at the time, I knew I shouldn’t discuss politics. But no one told me why. That’s the way it was. My family was not what you could call dissident. But we had access to illegal publications and we helped distribute them. We used to buy paper in large quantities to print the fliers. And that was enough to attract the attention of the secret police”.

From the age of seven or eight, Pavel was convinced that, once he became an adult, he would end up in prison for his ideas or his faith. But, in the blink of an eye, on 9 November 1989, his fear disappeared. Apart from the supporters of the regime, that was crumbling 600 kilometers away, the majority of the population was experiencing a collective euphoria that would last almost four years. "It was a time like no other”, says Pavel, “either before or after”.

These four years of enthusiasm included the collective resignation of Czechoslovakian communist leaders, the amendment of the Constitution to abolish the dominance of the Communist Party, the election of the dissident writer Vaclav Havel as president of the country, and the "velvet revolution", the birth of two republics, Czech and Slovak.

However, after four years, the euphoria gave way to a different feeling: "People realized that freedom is not so easy," says Pavel. The transition from a centralised planned economy to a market economy was very complicated: "Political power turned into economic power".

On the streets of Rome

This was the period of Pavel's adolescence and education, but also a chance to travel. For the first time in his life, he could go abroad. He caught a bus, and travelled through Austria as far as Italy. He was enchanted by the new landscapes and discovered a western lifestyle. "You'll find this funny," he says, "but it was the first time I'd seen clean public toilets on a motorway. That couldn’t happen in our country, where everything was dirty, and ugly. This is one of the characteristics of totalitarian countries: you don’t find beauty in public spaces".

At the age of 15, Pavel found himself wandering the streets of Rome. One of his first stops was at the tombs of the first martyrs. "I felt the connection between these martyrs of the early Church and our martyrs. It was very strong". In St. Peter's Square, he looked up at the windows of Pope John Paul II, remembering how much the Pope had done for the freedom of Christians. There were few international radio stations back home, but despite its frequencies being disturbed, Vatican Radio, brought with it the Pope's voice and a global outlook. "We watched the news on Czech TV. It was very controlled. So about half an hour later we listened to radio broadcasting from the West. That way knew what was really going on. We became so skilled at doing this that, eventually we could watch Czech TV and understand what was actually happening. It was almost laughable.”

Separated yet together

A few months after he returned home, a friend told Pavel that Slovakians wanted to create a separate country. "We started crying because we didn't understand. We were 16. Why did they want to cut our country in two?". At the time many Czechs were living in Slovakia, and vice versa. "I prayed this separation would be a peaceful one", recalls Pavel. Between 31 December 1992 and 1 January 1993, the official date of the separation, Pavel was in Vienna, Austria, at the annual gathering of Taizé. "Even during the prayer vigil in Vienna we were separated", he says, "the Czechs on one side and the Slovakians on the other. We asked the organizers if we could be together. We explained how there would be no fighting.

At midnight, exactly when Czechoslovakia was being divided, we celebrated a Mass together with the friars of Taizé. The message was clear: "We promised each other that even if we were separated politically, we would always remain friends".

The last a wall to come down

When you grow up in a totalitarian regime, perhaps one of the most difficult things is to open yourself up to others. At home, in the family, you could say whatever you wanted. A few close friends were included in this private circle. But outside this small group, Pavel kept quiet. "Throughout my childhood it felt like there was a wall inside my head," he says. Even after 1989, that invisible wall was still there: "You often met former secret police members on the streets, or in shops.” You could also encounter former local leaders of the communist regime.

Pavel felt trapped by this oppressive authoritarian presence. He’d been free since November 1989, and that was a fact. But he still wasn’t free from his inner prison, and that meant he couldn’t do anything. “One day I went to pray in an old 13th century abbey”, he says. “I was alone, and without knowing why, I suddenly started crying. I heard my inner voice tell me I had to forgive. I convinced myself I had to pardon all those who had hurt my family.” Pavel closes his eyes and repeats the word "Forgiveness”. “That was when I felt truly liberated”, he says, “when I realized I had the power to forgive.”

That was the day "the wall in my head came down".

Thank you for reading our article. You can keep up-to-date by subscribing to our daily newsletter. Just click here