Woven art

by Paolo Ondarza – Vatican City

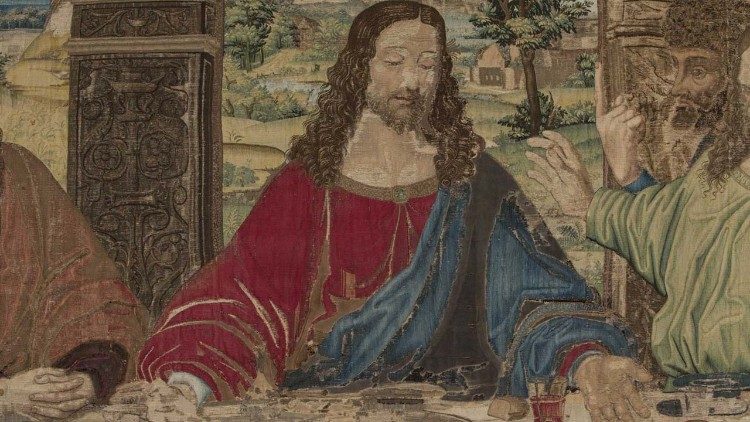

Enigma and mystery, that like a halo surround the person of Leonardo da Vinci, emerge from the interwoven strands of silk used to make the tapestries on exhibit in the Raphael Room in the Vatican Museums’ Pinacoteca.

The King who wanted Leonardo in France

It’s a reproduction on cloth of the Last Supper painted on the wall of the convent dining room of Santa Maria delle Grazie in Milan by the Renaissance genius. King Louis XII fell in love with the painting so much that he proposed that it be dismantled and transported from Milan to Paris. That, however, would remain a dream for the French crown, until Francis I ascended the throne and decided to commission a transposition of the painting on fabric.

The two versions of the Last Supper

Although some doubts still remain regarding the client’s identification and the place and year it was produced, the tapestry can definitely be dated sometime between 1516 and 1524: the period of Leonardo’s stay in France. It cannot be excluded that the artist may have admired the precious cloth with his own eyes, but the hypothesis of his direct involvement in designing the cartoon seems unfounded. Differences between the painting and the tapestry catch the eye immediately. The minimalism and the almost metaphysic atmosphere of the Last Supper of Santa Maria delle Grazie fade away in the Vatican Museums’ woven work which portrays a Renaissance taste with a French flair: there are three arches in the background, an echo of Lombard architecture, beyond which a landscape dominated by ancient fortresses can be seen.

Gold and silver threads

The refinement of the workmanship indicates Brussels as the place of production. All the threads, made of either gold- or silver-covered silk, trace the figures of the apostles, but also the salamanders and wings, evident references to Francis I and his mother, Louise of Savoy. Woven into the textile are initials, embedded in a sea of symbols, that allude to the King and his wife, Claudia who died in 1524. Intertwined knots stand out. On the one hand, bring Leonardo’s “knots” or “ties” to mind; but on the other hand, are allusions to the Savoy family or the Franciscan order.

A gift for the Pope

In 1533, the monumental tapestry departed for Rome, becoming separated from the rich and outstanding collection of the King of France. Francis I himself gave it to Pope Clement VII as a gift on the occasion of the sumptuous marriage celebrated in Marseilles between Catherine de’ Medici (the Pope’s niece) and the king’s second-born son, Henry of Valois. The memorable wedding was described in great detail by the chroniclers of the day: after the Sack of Rome in 1527, this wedding sealed the alliance between France and the Papacy, an anti-Habsburg move. The Pope reciprocated the tribute of the tapestry with a cetacean horn gilded by the famous goldsmith Tobia da Camerino. This horn was presented as a “unicorn horn” which, according to an ancient tradition, was believed to be a potent antidote in protecting one against poisoned food.

Exhibited on grand occasions

Da Vinci’s Last Supper tapestry was conserved in the Vatican’s Floreria and used on special occasions during the liturgical year. During the Corpus Christi procession it was hung along the Scala Regia along the way leading from the Sistine Chapel to Saint Peter’s Basilica. On Holy Thursday, instead, it was displayed on the walls of the Sala Ducale while the evocative ritual of the washing of the feet was performed.

This textile masterpiece has remained in an excellent state of conservation down to our day. In the 1700s, Pope Pius VI had a copy of it made by the painter Bernardino Nocchi. It was transposed into a tapestry by Felice Cettomai, then Director of the Pontifical San Michele Manufactory. From that moment on, this copy was used during papal ceremonies, thus preserving the original from exposure to the atmospheric elements.

A giant to restore

The original Francis I tapestry has undergone several restorations, the last in 2019 when, prior to departing for an exhibit in France, the tapestry was lined with nylon tulle, dyed previously by the technicians in the Tapestry and Textiles Restoration Laboratory.

Measuring 4.9 meters high (16 feet) and 9 meters long (29.5 feet), the monumental and delicate Last Supper tapestry is not easy to move or “be moved”. The experience, dedication and professionalism of the Vatican restoration workers are, however, a guarantee, drawing on centuries of knowledge and tradition. The Papal tapestry collection, in fact, numbers almost three hundred pieces and dates back to the 1400s. From the beginning, the Popes, with farsighted vision and a pioneering approach to “cultural heritage” entrusted the ongoing care of these artifacts to a “conservator”.

Raphael and the Vatican collection

“The Vatican collection”, recalls Alessandra Rodolfo, Curator of the Department of Tapestries and Textiles, “exploded at the time in which Raphael designed the cartoons for what would later be considered an undisputed masterpiece of world-wide fame”: the series of ten tapestries depicting scenes from the Acts of the Apostles, commissioned by Pope Leo X (de’ Medici) and produced in the Flemish workshop of Pieter Van Aelst’s, who became the “Pope’s tapestry maker”.

“The tapestries”, she continues, “were destined to complete the iconographic plan of the Sistine Chapel on the lower part of the walls corresponding to the painted curtains – on the ceiling, episodes from Genesis, painted by Michelangelo; the middle register of walls covered by the stories of Moses and Christ completed by various 15th-century artists; the lower register would depict the account narrated in Acts of the spread of Christianity through the two princes of the Apostles, Peter and Paul, with the Universal Judgement, painted later by Michelangelo, completing this grand narrative”.

The Sistine tapestries revolutionize art

“Only by admiring them in the Sistine Chapel can you fully understand Raphael’s tapestries”. This is exactly what happened for a week in February 2020 when the ten masterpieces were once again mounted on their hooks in the Cappella Magna, thus renewing the competition between Michelangelo and Raphael Sanzio and their ability to capture beauty. “At the time in which these tapestries were created”, Alessandra Rodolfo continues, “they unhinged the canons of art”. The transfer of Raphael’s cartoons to Brussels profoundly impacted 16th- century European culture. It was an era in which the art of tapestry making was considered more refined and superior to that of painting. It in fact represented a status symbol, a vehicle for mobile iconography: it could be moved, rolled up, exhibited indoors or outdoors, allowing for a wider public – and on multiple occasions and celebrations – to admire the prestige of the reigning pontiffs.

Sx times the cost of Michelangelo's frescoes

Even the cost of a tapestries was far greater than that of a fresco. Raphael’s tapestries cost six times more than Michelangelo’s frescoes on the Sistine Chapel ceiling. “The Pope”, Alessandra Rodolfo explains, “had to invest a lot of money, paying large sums in advance, to the point that he went into debt. To pay off the huge debts that Pope Leo X left after his death, and to pay for the Pontiff’s funeral, Raphael’s tapestries were used as collateral with the famous German banking and entrepreneurial Fugger family”.

Manufacturing costs also drove the cost up – beginning with the dying of the threads with natural dyes. Some of these threads contained a silk core covered with gold or silver foils beaten by specialized craftsmen known as battilori .

The original colors seen on the back

To have an idea of the original beauty and brilliance of the tapestries, they need to be observed from behind where the light has not faded the original color and brilliance over time. An expert tapestry makier could produce approximately one square meter per month. In addition, the work began with an artist tasked with designing the cartoons.

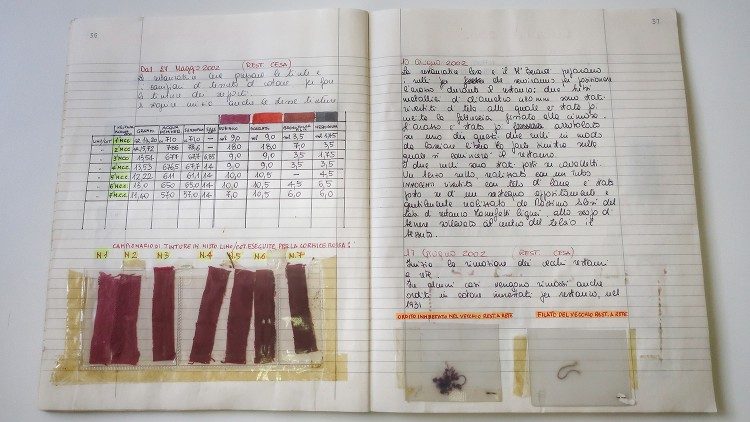

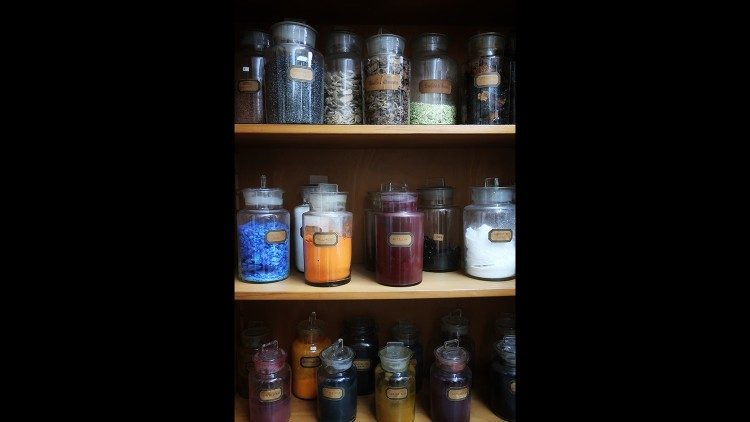

A tapestry is an extremely delicate work. Made to be hung, it endures the constant tension to which the fabric is subjected. Just as laborious and complex is the work needed to conserve it: from removing dust, to sponging, to being washed in large tubs with ionized water and detergents recommended by the Vatican Museum’s Cabinet of Scientific Research, to drying it out on a large grill, and finally to the point of repairing damaged places using colored threads obtained by consulting over one thousand recipes jealously guarded in the notebooks of the Vatican restoration workers.

Vatican warehouse

Elements such as light and temperature ideal for conservation must be carefully monitored. The tapestries are either kept in the Vatican storerooms on sliding frames, designed in the 1930s by the founder of the Vatican Restoration Laboratory, Biagio Biagetti, or they are rolled up and wrapped in white, breathable sheets. Restoring a tapestry requires considerables economic resources, in addition to a great deal of time and patience. Just think that the restoration of the ten Raphael tapestries began in 1981 and was completed only a couple of years ago.

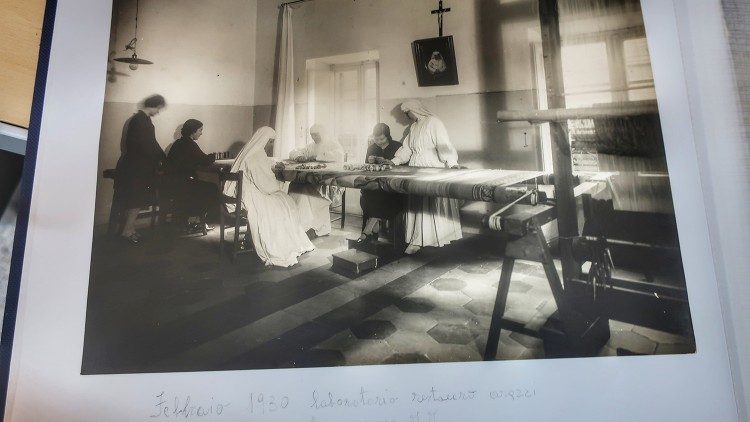

A team of women

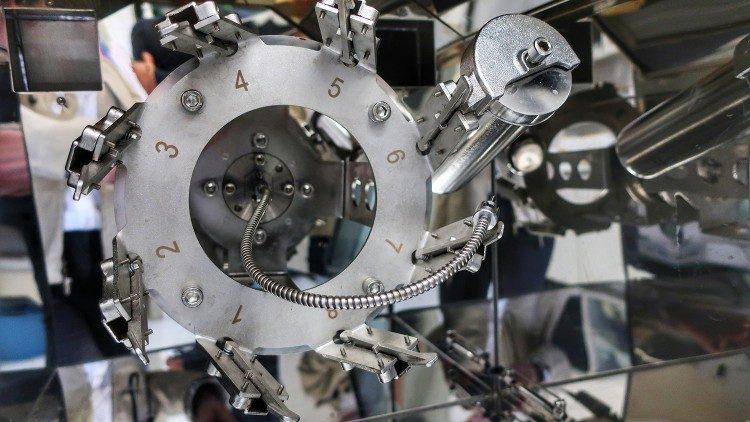

Heir to the Pontifical Tapestry Factory founded by Pope Benedict XV in 1920, and the even older Roman Tapestry Manufactory of San Michele founded by Clement XI in 1711, the Tapestry and Textiles Restoration Laboratory, historically the first of the Museums’ restoration departments, is made up of seven professionals, three of whom are women religious – the Franciscan Missionaries of Mary to whom Pope Pius XI, in 1926, entrusted the care of these precious works of art. Spools of colored threads, antique looms bearing witness to the older Vatican tapestry school, teamwork, painstaking patience and enormous passion are woven together, like a piece of cloth, in the fascinating rooms in which tradition and innovative technology are engaged in a fruitful dialogue so as to guarantee the transmission of one of the world’s most precious, fragile and unique heritages to future generations.

Thank you for reading our article. You can keep up-to-date by subscribing to our daily newsletter. Just click here