The Pharaohs at the Papal Court

By Paolo Ondarza – Vatican City

“The Pope ordered his Camerlengo not to buy any more Etruscan, Greek or Roman objects, only Egyptian ones.” It is 2 April 1838. Barnabite Father Luigi Ungarelli, commissioned by Gregory XVI to set up the new Egyptian Museum in the Vatican, enthusiastically writes to his instructor and friend, Ippolito Rosellini. The latter, an eminent Egyptologist from Pisa, Founder of Italian Egyptology, first professor in the world awarded with a chair in Egyptology, was the Pontiff’s first choice to develop the enterprise, but he had to decline the invitation, proposing the name of his favorite student.

From mystery to science

With the foundation of the Gregorian Egyptian Museum on 16 February 1839, the Vatican played an active role in the consolidation of the international archaeological movement thanks to which the science of Egyptology was born. From that point on, what had been matter for "mystery" became science. The period was launched by the chance discovery of the Rosetta Stone during the Napoleonic campaign in 1799. This granodiorite artefact which contains the text of a decree issued in 196 B.C. in three different scripts (hieroglyphic, Demotic, and Ancient Greek), honors the Pharaoh Ptolemy V Epiphanes and enabled the ancient Nile Civilization, “mute” and shrouded in mystery until then, to “speak”.

In fact, in 1822, studying the stele allowed the Frenchman Jean François Champollion to begin deciphering the enigmatic writing of the ancient Egyptians. Egyptomania exploded – a feverish curiosity and desire to know raged among scholars, antiquarians and collectors. The scientific publication Description de l'Égypte (Description of Egypt), edited by about 160 savants (scholars) during the Napoleanic expedition is testimony to this.

A hieroglyph praises the Pope

The strong intuition, sensibility, culture and interest in antiquity of Pope Gregory XVI provided the decisive impulse. He was a member of the Cappellari family, a Camaldolese monk, elected Pope in 1831 and founder of three Museums in the Vatican – the Gregorian Estruscan Museum in 1837, the Gregorian Egyptian Museum in 1839 and the Gregoriano Profano Museum in 1844. The Holy Father used his own personal finances from 1838 to acquire all the Egyptian works contained in collections in Rome or that were on the antiquarian market. A bronze medal and a hieroglyphic inscription, written by Ungarelli that runs the length of the upper molding in the second hall of the Gregorian Egyptian Museum, commemorates its inauguration: “His Majesty, the Supreme Pontiff, the munificent Gregory, sovereign and father of the Christian peoples of all countries, to make the city of Rome shine with his munificence, has collected the great and beautiful ancient Egyptian figures and created this place in the year 1839, in the month of his Coronation, on the VI day of God the Savior of the world (which is also) the day of the coronation of His Majesty, in the ninth year (of his reign).”

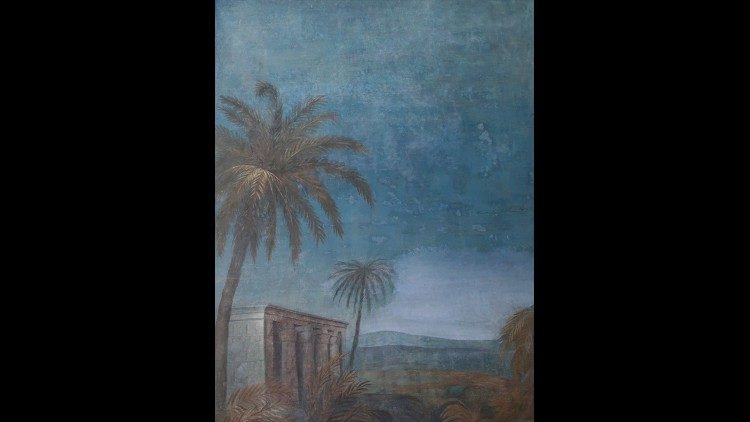

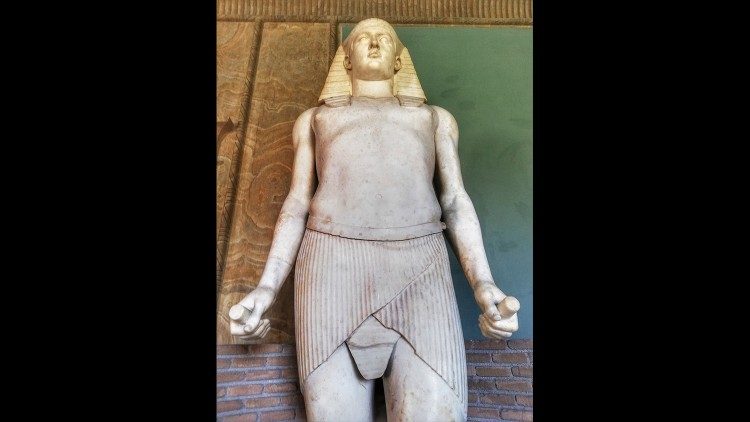

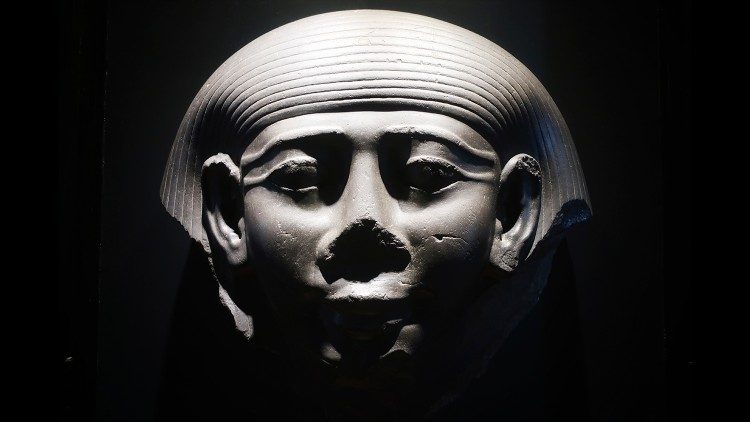

One of the unique characteristics of the collection, situated in Pius IV’s former apartments in the Belvedere, is its territorial identity. Unlike the other large collections of Egyptian artifacts that were being formed in all of Europe in those years in the wake of archeological campaigns and frenetic acquisitions, the Vatican collection gathered artifacts preserved in the Urbe (city of Rome) since the time of the Roman Empire. They were Egyptian originals or Egyptian works created in ancient Rome to decorate the villas of the Patricians. Of particular significance are the remains from Hadrian’s Villa in Tivoli, as well as the majestic statue of Osiris-Antinous or those transported from the New Palace of what was at that time the Capitoline Museum.

The obelisk that never arrived

The curator of the Vatican Museums’ Department of Egyptian and Near Eastern Antiquities, Alessia Amenta, recalls a lesser-known detail regarding Pope Gregory XVI’s interest in Egypt: the so-called Roman Expedition. “At the behest of the Pontiff, from December 1840 to August 1841, three ships called Fedeltà, San Pietro and San Paolo (Loyalty, St Peter and St Paul), departed from Rome’s Ripa Grande Port to sail the Nile to Upper Egypt with the task of bringing artifacts and scientific documentation – from the Tiber River to the first cataract of the Nile was 1165 km (about 724 miles). The enterprise is even commemorated with an inscription dated 21 January 1841 in the Temple of Isis on the Island of Philae.”

Few people know that in addition, “as a crowning achievement to the museum’s design, Luigi Ungarelli had planned that the oldest preserved obelisk, measuring more than 20 meters (almost 66 feet) and dating back to Pharaoh Senusret I, would be placed within the Vatican in the middle of the Pine Cone Courtyard where today the Arnaldo Pomodoro sculpture is located. With the scholar’s death in 1843, however, this grandiose project vanished as recounted in an article published in L’Osservatore Romano on 2 September 1945 entitled ‘An obelisk that never arrived’.”

The serious involvement of the Papal State in the rise of Egyptology as a science is also evidenced by the gift made by the British Museum in 1944 of a mold of the Rosetta Stone which was immediately exhibited in the new Gregorian Egyptian Museum.

A vibrant place

Since its foundation, therefore, the Vatican collection contributed to the huge international Egyptological movement and consolidation. “Today, the Gregorian Egyptian Museum”, Alessia Amenta continues to explain, “is, as it was at the time of its foundation, a vibrant place of research, with its door ever open to international dialogue and exchange. It is involved with and avails itself daily of the precious collaboration with the Vatican Museums’ Diagnostic Laboratory for Conservation and Restoration and with many restoration laboratories, and extraordinary professionals. Each single restoration becomes a unique opportunity for study and research.” The curator cites various international studies: from the Vatican Mummy Project, regarding the human and animal mummies, carefully wrapped in linen cloth, which even allowed the study of the DNA of the bodies which survived for millennia; to another called the Vatican Coffin Project regarding the wooden and multi-colored so-called “yellow sarcophagi”, recognized as being the oldest wood paintings in history.

From ancient Egypt to the Middle Ages

Studying the paint stratigraphy has brought to light the knowledge of a painting technique equal to the process adopted by Giotto in the Middle Ages and used by his skilled laborers. “It was a discovery that filled a huge gap between the ancient period (the ancient Egyptians did not leave anything written relative to painting techniques) and the medieval age when, for the first time, the painting technique for use on wood was codified in the book Il libro dell’arte o Trattato di Pittura (The Book of the Art or Treatise of Painting) by Cennino Cennini, a fourteenth-century Tuscan painter.” Even visually, the yellow background of the sarcophagi under study reminds one of the golden background of medieval panels, which demonstrates the same intention of transfiguring what is depicted into an otherworldly dimension.

The sarcophagus and the voyage to eternity

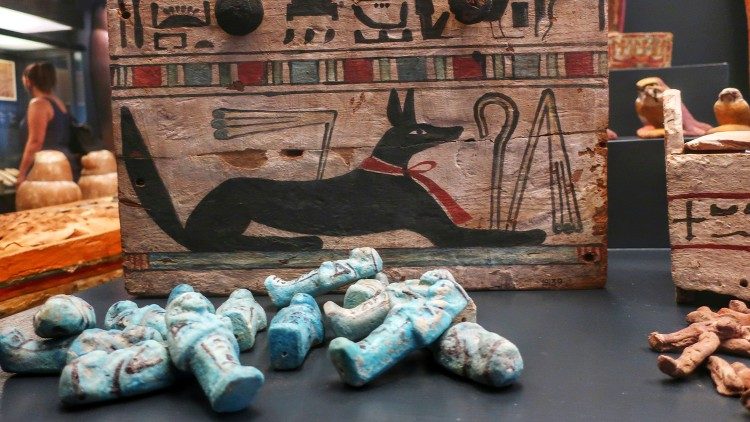

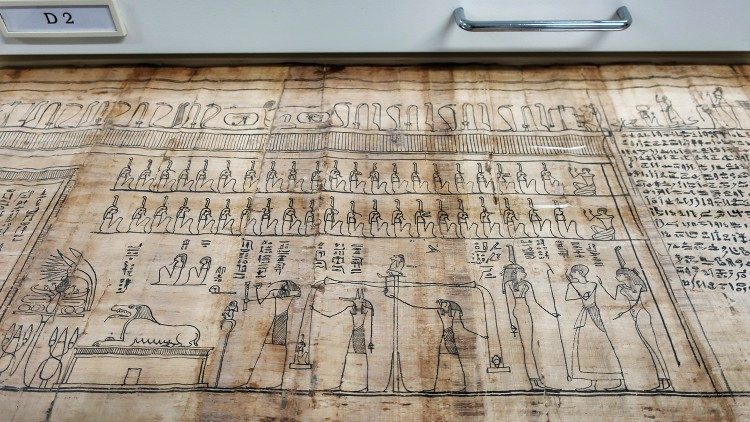

For the ancient Egyptians, the sarcophagus was the microcosm in which the mummy, the most precious object of the funerary apparatus, was kept and preserved. It insured eternity to the individual. Within it, the deceased would be born again each day with the rising of the sun. Jewels, amulets, shoes, and objects of personal use made up the paraphernalia that would accompany the person on his or her voyage to the afterlife. “The funerary papyri,” Alessia Amenta continues, “contain magical formulas and rituals that would guarantee that the deceased reach eternity” – a sort of “passport” for beyond the grave. Among the iconographic images is the divinity Osiris, god of the Underworld and judge of the dead, before whom the heart of the deceased would be weighed on a balance to evaluate his or her conduct. The heart was the only organ that was left inside the mummy. Lungs, liver, stomach and intestines were instead extracted and placed by the embalmers in canopic jars at the moment the body was mummified so that they would be reactivated in the afterlife.

Between crocodiles and lionesses

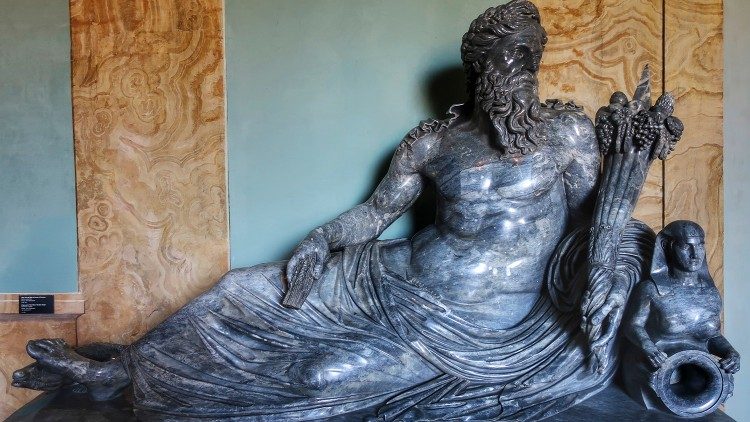

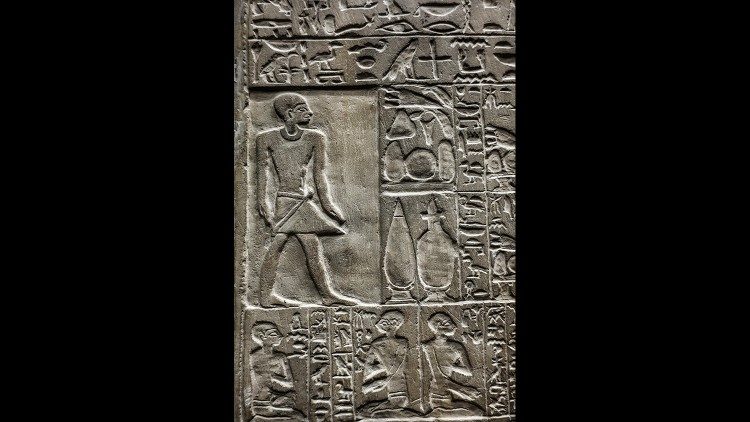

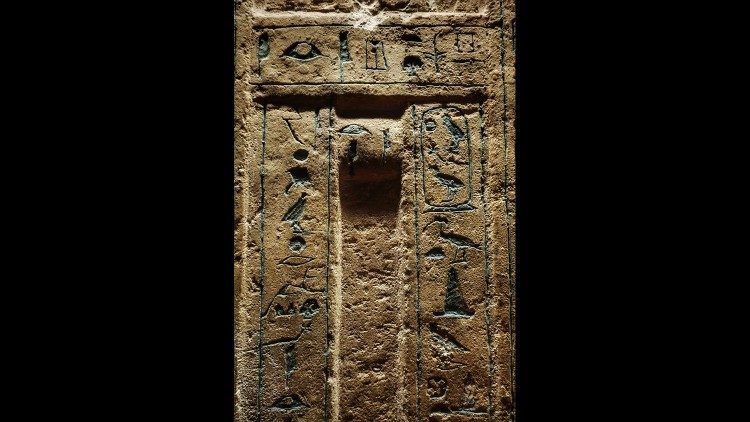

In the Egyptian Museum’s halls, which even today preserve the exotic decorations of the eighteen hundreds in the first rooms, the eye is bombarded by a lot of stimuli: the hieroglyphics inscribed on the robe of the statue in Udjahorresnet, an important character of the 6th century B.C., have allowed the narration of stories from the period of the Persian conquest of Egypt that took place in 525 B.C.; the small wooden model of a boat from a Theban sepulcher from the 11th Dynasty (end of the 3rd millennium B.C.); the imposing statue of the Nile, of Roman production from the 1st or 2nd century A.D., at whose feel a crocodile is sculptured, sacred to the god Sobek, deity of water and floods.

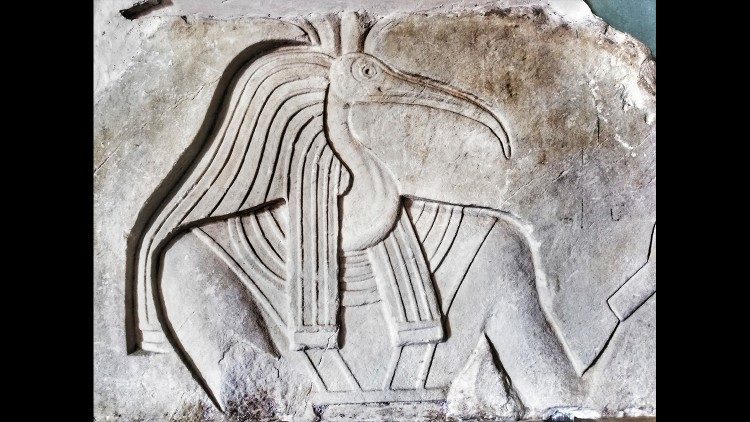

Fascinating are the suggestions that emanate from the animal sculptures, from the wooden sarcophagi decorated with cat mummies or of the anthropomorphic statues. Mario Cappozzo, Assistant Curator of the Department of Egyptian and Near Eastern Antiquities comments: “Our ‘Sekhmet Project’ studies the hundreds of lioness statues traced to the goddess Sekhmet and her most ferocious countenance. All of them come from the extraordinary scenery of the funerary temple of Amenhotep III in Thebes (Waset). In ancient Egypt, gods co-existed together, represented under human, animal, or mixed forms. In particular, these bizarre beings which were so enchanting to the ancients, were none other than depictions of various aspects of the god,” Mario Cappozzo concludes.

From pharaohs to Patriarchs

“I will now speak about Egypt, because this place possesses many wonderful things and presents monuments that surpass every story and comparison with any other place.” This awe expressed by Herodotus of Halicarnassus in The Histories is an experience that is renewed amidst the halls of the Gregorian Egyptian Museum, where the monuments tell of the incomparable civilization of the pharaohs and the story of a country that was crucial to the history of salvation: a land traversed by the biblical Patriarchs and that was a place of refuge from persecution for the Holy Family.

Thank you for reading our article. You can keep up-to-date by subscribing to our daily newsletter. Just click here