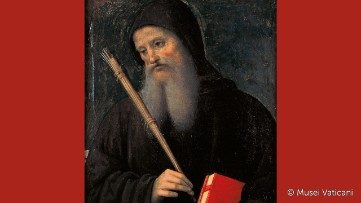

St. Benedict, Abbot, Patron of Europe

The thought of St. Benedict is the lifeblood of Europe

Born in the central Italian mountain town of Norcia (Nursia) around AD 480, St. Benedict became one of the most important catalysts for the creation of a new European culture after the fall of the Roman Empire in the West (traditionally dated to AD 476). The system of monastic life he developed and nourished spread centers of prayer and hospitality throughout the continent. Benedictine monasteries were not only spiritual and cultural centers, but also a source of sustenance and relief for pilgrims and the poor.

Bright Star in a Dark Century

St. Gregory the Great – who wrote the only ancient biography of St. Benedict that we have – called St. Benedict “a bright light” in an age marked by the most serious crisis. From his youth, Benedict’s life was marked by prayer. His wealthy parents send him to Rome to provide him with adequate training. There, however, Benedict found young people shaken, ruined by the ways of vice. So, he left Rome for a place called Enfide (modern-day Affile in central Italy), and then lived as a hermit for three years in a cave at Subiaco, which would become the heart of the Benedictine monastery Sacro Speco. This period of solitude preceded another crucial milestone on Benedict’s journey: his arrival at Monte Cassino. There, among the ruins of an ancient pagan acropolis, St. Benedict and some of his disciples built their first abbey.

The rule

Benedict composed his Rule around AD 530. It is essentially a manual, a code for monastic life. Written in a familiar style, Benedict throughout the prologue and 73 chapters of the Rule exhorts his monks to reach out with “the ear of the heart” to “never despair of the mercy of God”: “Listen carefully, my child, to your master's precepts, and incline the ear of your heart (Prov. 4:20). Receive willingly and carry out effectively your loving father’s advice, that by the labor of obedience you may return to Him from whom you had departed by the sloth of disobedience.”

Ora et labora – Pray and work

“Idleness,” writes St. Benedict in the Rule, “is an enemy of the soul; That is why the brothers have to devote themselves to manual work, in some hours, in others, to reading books containing the word of God.” Prayer and work are not in opposition, but establish a symbiotic relationship. Without prayer, it is not possible to encounter God. The monastic life, however, defined by Benedict as “a school of the service of the Lord,” cannot be without concrete commitment. Work is an extension of prayer. “The Lord,” St. Benedict reminds us, “expects us daily to respond with facts to the doctrines of his holy teachings.”