Vatican Museums: Laocoön and 'the Arm of Memory'

By Paolo Ondarza - Vatican City

Disbelief and helplessness in the face of a tragic fate that explodes unexpectedly: these are the feelings shared by two figures distant in time, but whose stories were incredibly intertwined and never parted. Their meeting occurred thanks to a seemingly anonymous sculptural fragment.

In the workshop of a stonecutter

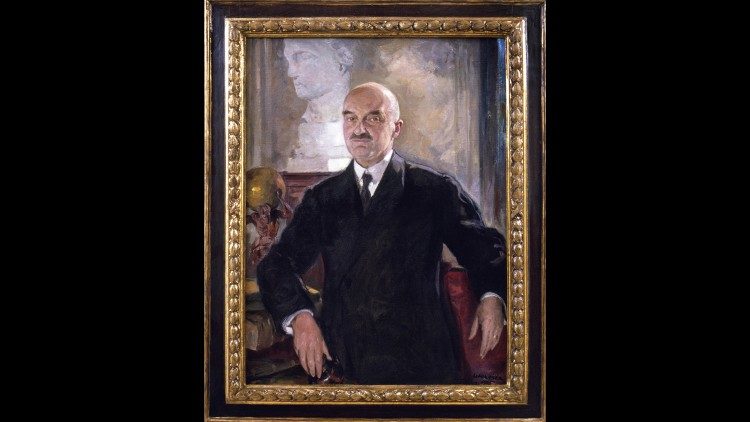

The first is the internationally renowned Jewish scholar, art dealer, and archaeologist, Ludwig Pollak, known for the significant discovery in Rome of a marble copy of Myron's Athena now at the Liebighaus in Frankfurt—a friend of Sigmund Freud who was active in the circle of great collectors such as J.P. Morgan, Stroganoff, Barracco, and Bode—who died in the Auschwitz Birkenau extermination camp in 1943.

Forty years earlier, while walking through the streets of the Oppian Hill during one of his usual inspections among excavations, junk dealers, and marble workers, in the workshop of a stonecutter on Via delle Sette Sale, he noticed and purchased a marble arm from the excavations on the nearby Via Labicana.

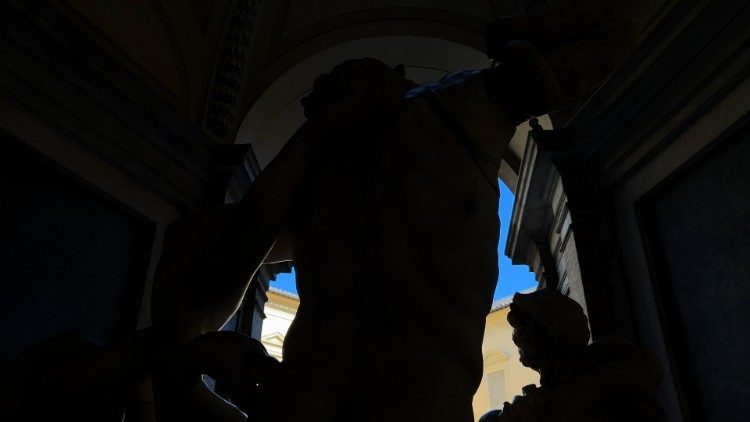

His infallible intuition immediately led him to identify the artifact as belonging to Laocoön, the iconic sculpture of the Vatican Museums.

The sacrificial victim

The second character is precisely the Trojan priest, a foundational sacrificial victim of the birth of Rome, unheeded in his appeal to his fellow citizens not to trust the wooden horse.

Laocoön was punished by the goddess Athena who had him crushed along with his two sons by two enormous serpents emerging from the sea.

The monster

It changes face and skin, as reptiles do in nature—that monster which terrifyingly, inexplicably, can burst into the routine of human life.

In one case, it had the brutal face of Nazism; in the other, it was the instrument of an unimaginable, undeserved, and fatal divine punishment. In both cases, it tragically also swallowed even the slightest hope of staying alive.

A repetitious tragedy

It is also the story of our days, notes Giandomenico Spinola, Deputy Artistic and Scientific Director of the Vatican Museums, formerly in charge of the Archaeology Department.

"Today in the Holy Land, people should simply get up in the morning, think about grocery shopping, and take their children to school, continuing their daily lives, from both sides,” he said. “I don't think anyone likes war; it's a great tragedy. Pollak's story is a testimony to that. Even then, for illogically religious reasons, abuses and murders were committed for something that has nothing to do with religion or everyday freedom, or anything that can justify the death of unarmed people."

A great eureka

Striking is the apparent nonchalance with which Ludwig Pollak, in a letter from 1903, preserved at the Zentralarchiv in Berlin, reports the shocking discovery of the arm to his friend, the German art historian Wilhelm von Bode, founder the following year of the Kaiser-Friedrich-Museum.

"Pollak," says Federica De Giambattista, a PhD in Art History at the Sapienza University of Rome and expert on the Prague-born archaeologist, "due to his role as an expert art dealer, was in contact with some of the main private collectors and directors of international museums. In a letter to Wilhelm Bode, among other things, he reports having purchased the right arm of the Laocoön. He calls it 'a great eureka,' a beautiful discovery and writes: 'Now it is my property!' When Pollak uses exclamation points, it's because he is aware of communicating something very important."

The close connection with the Laocoön is also attested by two terracotta sketches, which, observes De Giambattista, "were part of the rich collection of sketches from the 16th and 17th centuries of Ludwig Pollak and that today are preserved in the collections of the Princeton University Art Museum.”

Athena in the kitchen of Count Stroganoff

His particular talent, demonstrated on several occasions in recognizing works of art, earned him numerous commissions from wealthy private collectors.

Chief among them was his fruitful relationship with Count Grigorij Stroganoff, for whose famous collection he personally curated the catalogue. In a female statue deemed fake and therefore placed in a service area adjacent to the kitchen of the Palace on Via Gregoriana belonging to the noble and diplomat Russian, Pollak identified a famous Athena: the Roman replica of the bronze group of Athena and Marsyas by Myron, which was completed with the Marsyas of the Vatican Museums.

"That work," recalls De Giambattista, "was chosen as a collection brand by Pollak; in fact, it accompanied the letters L.P. that the archaeologist printed on all the Old Masters drawings he preserved."

The market and ethics

While convinced that private collections, more than museums, preserved the soul of taste and passion for the ancient, Pollak showed high professional ethics when he realized that the purpose of reassembling the famous group of Laocoön merited a foregone profit.

He made a first visit to the Vatican Museums in 1904, hosted by the future director and friend Bartolomeo Nogara: the arm seemed at first glance too small and was thought to come from a reduced-format copy of the same Laocoön.

The seven arms of Laocoön

It is estimated that at least seven arms were made over the centuries to complete the sculpture executed in Rhodes between 40 and 20 B.C.

When it was unearthed in 1506 at the vineyard of Felice de Fredis, an officer of the Apostolic Chamber at the time of Pope Julius II and identified by Giuliano da Sangallo and Michelangelo in the marble described by Pliny, the statue of Laocoön was substantially intact.

Among the missing parts, the right arm was notably absent. There followed a lengthy debate about whether it was originally bent behind the shoulder or extended in a heroic, dynamic gesture.

The arm behind the pedestal

Faithful to the latter idea was the first integration in terracotta, the work of Fra Giovanni Agnolo Montorsoli, a pupil of Michelangelo Buonarroti.

Another arm was later made, this time bent, according to the popular version by the artist of the Last Judgment and closer in pose to the original. Another famous version is the eighteenth-century one by Agostino Cornacchini to which the unfinished arm currently placed on the back of the pedestal of the Laocoön in the Octagonal Courtyard can also be traced.

The gift to the Pope

The Pollak arm reopened the debate. It was soon understood that the apparent disproportion relative to the body of the statue was due to the progressive erosion of the shoulder caused by the various attempts at reconstruction carried out over the centuries. The fragment found at the stonecutter’s shop on the Oppian Hill was therefore recognized as pertinent.

In 1906, 400 years after the discovery of the Laocoön, the Bohemian antiquarian decided to donate the "jewel" to the pontifical collections. That gesture corroborated the partnership with Nogara and earned the art dealer the Grand Cross of Culture awarded by Pope Pius X, today preserved in the Barracco Museum.

The first unconverted Jew awarded the papal medal

It was the only case of an unconverted Jew receiving such an honor, and it was also one of the few official tributes granted in Pollak's lifetime for the incredible discovery.

A year after his death, in 1942, he also enjoyed the satisfaction of seeing his discovery recognized by the famous archaeologist Ernesto Vergara Caffarelli, as attested by two articles in L'Osservatore Romano and Corriere della Sera. However, the Prague native never saw "his" arm reunited with the Laocoön.

A success not enjoyed in life

The reconnection would indeed occur fifteen years later, in 1957–59, thanks to the intervention conducted by Filippo Magi, who removed all the non-original integrations, according to the principles of modern restoration.

They are a vivid testimony to the historic shots preserved in the Phototeca of the Vatican Museums, a true treasure chest that preserves a heritage of hundreds of thousands of images, including negatives, films, and glass plates: 9,000 of which are accessible online by everyone.

The photographic heritage entrusted to the Phototeca Office consists of approximately 350,000 original black and white negatives (with respective print positives), 70,000 color images on film (partly also acquired in digital format), and 49,000 glass plates that make up the collection of historical funds.

25 diaries to preserve memory

Recording every detail, even insignificant ones, and keeping a memory of everything to not forget was an imperative in Ludwig Pollak's professional activity. Countless are the photographs he took and offered for sale of art objects and antiques.

Twenty-five handwritten diaries are preserved, together with the Library and the archive of the Prague merchant, at the Barracco Museum in Rome, of which he was honorary director starting from the death of the collector and friend Giovanni Barracco in 1914.

"When on his deathbed, on December 29, 1913, Barracco expressly asked Ludwig Pollak to take care of his museum and his collection when he would no longer be around," recalls Lucia Spagnuolo, curator in charge of the Museum of Ancient Art Sculpture Giovanni Barracco, "naturally Pollak accepted, provided his service would be absolutely free of charge. The Museum, precisely because of this very close relationship that existed between the two, has preserved, by the will of Pollak's only heir, Mrs. Margarete Süssman Nicod, the materials coming from the Pollak estate, i.e. documents, photographs, and handwritten papers that are part of today's Pollak archive, together with his library."

From these autograph texts, transcribed and partially published by Margarete Merkel Guldan in 1988 and 1994, and which "soon," assures Lucia Spagnuolo, will be published, emerges an awareness: memory has the power to prevent everything from being in vain.

Frictions with Nazism

Not coincidentally, when in 1935, even before the racial laws were enacted, he was expelled from the Hertziana Library—a place he had frequently visited—Pollak decided to photograph the letters he wrote with fiery tones to the new director, Leo Bruhns. Bruhns had replaced the first director of the Hertziana and dear friend, Ernst Steinmann.

"The letters to Leo Bruhns testify to one of the darkest pages in the history of our Library," says Tatjana Bartsch, deputy head of the phototeca of the Hertziana, where the originals of the missives are preserved. Pollak’s entry on April 19, 1933, was significant, when, at Palazzo Zuccari, headquarters of the German institute specializing in historical artistic studies, a meeting took place on the occasion of Hitler's birthday: "Hitler in the Hertziana (!!!) The foundation of the Jewish Henrietta Hertz!!!!"

"He could not believe indeed," continues Bartsch, "that such a celebration took place in a place so dear to him in Rome," founded only twenty years earlier by his collector and philanthropist friend.

Isolated and discriminated

From that moment on, Pollak would experience episodes of contempt and offense everywhere in official German circles in Rome. He took ever-greater refuge in his love for art and literature, in particular for his beloved Goethe, to whom he wanted to dedicate, at his own expense, a volume in Italian and German.

He was abandoned by many colleagues: only a few, among them the art historian Denis Mahon, with whom he shared a passion for Baroque art, continued to frequent him. The Eternal City had lost that welcoming warmth that had induced him in 1893 to choose it as his adopted homeland.

‘They won't come for me’

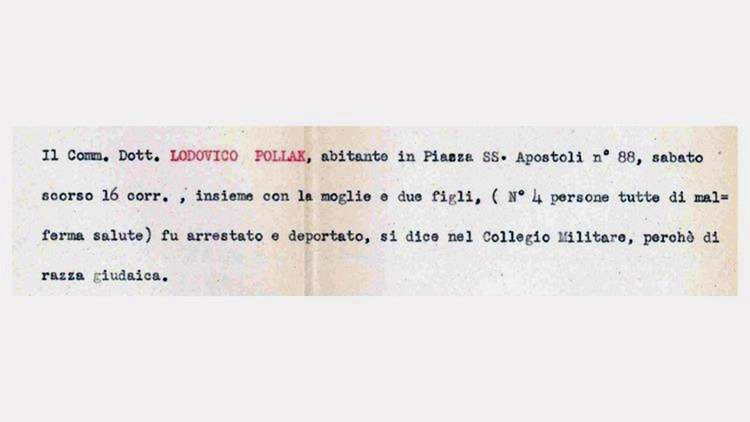

However, even up to the end, Pollak refused to believe that the Gestapo would come to pick him up at his home in Palazzo Odescalchi in Piazza Santi Apostoli.

The warnings he seems to have received from Jewish friends like Hermine Speier, who was brought to the Vatican by Pope Pius XI and Nogara to oversee the Vatican Museums' photographic archive starting in 1934 and who was baptized in 1939, or the art historian Wolfgang Fritz Volbach, who also worked in the Vatican during those years, went unheeded.

Refusal of the offer of shelter in the Vatican

Thanks to the mediation of Bartolomeo Nogara, a shelter had also been prepared for Pollak and his family in the Vatican. A car came to pick him up on October 15, 1943, to take him safely beyond the Tiber.

He did not accept that assistance, perhaps convinced that his life, marked by study and the search for ancient works, would never be disrupted by the fury of the Reich.

In the gas chambers of Auschwitz

The following morning, the seventy-five-year-old Ludwig fell victim with his two children, his second wife, and a thousand other Roman Jews to the Nazi roundup, and were sent to Auschwitz.

"The Arolsen Archives," says Federica De Giambattista, "preserve thirteen documents confirming the deportation of the four members of the Pollak family to Germany with a 'sonderzug', a special transport. Julia Süssmann was assigned to the Birkenau camp, where she died shortly after, while Ludwig, Susanna, and Wolfgang perished at the main extermination camp of Auschwitz. The lack of names in the surviving documents of the people being sought after is often due to the fact that they are incomplete sources, because many of them were destroyed by the SS before the liberation or evacuation of the concentration camps in the face of the advance of Allied troops and the Russian army. This is most likely the fate of the papers that must have recorded the entry and death of the Pollaks in the concentration camp."

Nogara's attempts to save him from death

"Nogara worked very hard until the end to save his life," specifies Giandomenico Spinola, highlighting the commitment of the Church under Pius XII in such a dramatic historical moment. "He intervened not only before, when Pollak was notified of the possibility of being picked up from his home, but also after his capture. He activated the Secretariat of State for his release and that of his family." The Nogara Archive papers preserved by the Vatican Museums testify to this.

In particular, in a letter to the German embassy, the future director of the pontifical galleries wrote: "Since the arrangement taken can be revoked, the undersigned makes a request to the higher German authorities, that an exception be made in favor of Comm. Pollak and his family... He and the three family members be returned to their home."

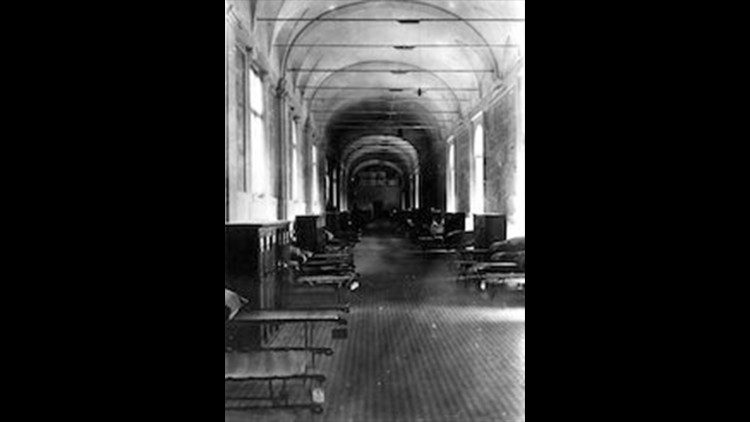

Jews hidden in the Pope's Museums

"In wartime, many people found shelter in churches and convents, but also inside the Pontifical State. Pollak," continues Spinola, "was invited to live in the Vatican. He was never asked to convert to Christianity in exchange for protection." Among other things, probably to provide shelter to some refugees and to store food supplies, "several exhibition areas here at the Museums were dismantled: the Chiaramonti Museum and the Lapidary Gallery became a place of shelter. Certainly, the Vatican was very active at the diplomatic and practical level."

"The Gestapo," adds the Deputy Artistic and Scientific Director of the Vatican Museums, "also seized some of Pollak's diaries. Those subsequent to 1933 have disappeared and this suggests that perhaps they contained writings deemed uncomfortable by the Nazis."

Remembering Pollak

"Until a few decades ago, the Pollak story was swept under the rug here at the Hertziana Library," admits Tatjana Bartsch. "Now our institute is changing policy. We are not guilty of what happened to so many Jews, but we cannot erase that dark era. Studying Pollak, I thought that if we can't remember him by praying at his grave, we can at least give him a place in our memory."

The stones and the "stumbling folder"

For this reason in 2022, precisely on the initiative of the deputy head of the phototeca of the Hertziana, who promoted a fundraiser within the institute, four stumbling stones ("Stolpersteine"), small brass plaques with the names and birth and death dates of Ludwig, his wife Julia and children Wolfgang and Susanna Pollak, were installed in front of Palazzo Odescalchi.

Among the important documents of the Hertziana Library is a "Stolperschachtel / Stumbling Folder," with a black label bearing the white inscription: "Ludwig Pollak. Born in Prague in 1868. Deported and murdered at Auschwitz in 1943."

An arm to remember the monster

The story and memory of Pollak also live on in the Laocoön. Thanks to the Jewish art dealer, the famous statue is today restored in its authentic message.

"He is not a hero who opposes death in a victorious form with an outstretched arm, but,” observes Giandomenico Spinola, “a man now without hope who, with his arm bent, defends himself from the attack of a monster. Like Pollak.”

Thank you for reading our article. You can keep up-to-date by subscribing to our daily newsletter. Just click here